This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 16, Issue 1, from 2003.

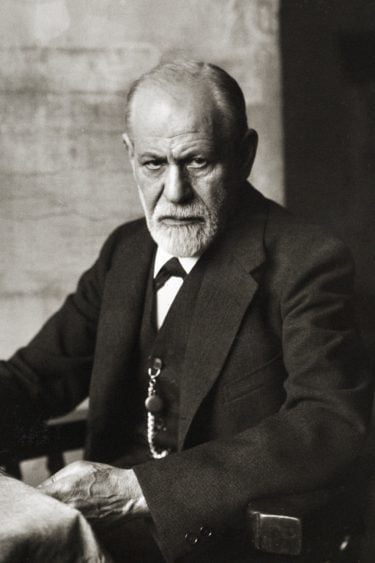

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) insisted that his postulations that are collectively known as psychoanalysis formed the basis for the science of psychology. Yet, ever since its beginnings in the early years of the twentieth century, there has been considerable argument as to whether psychoanalysis is even a science at all. Some claim that Freud’s work itself was entirely pseudoscientific in nature, and that later proponents of his theory have done little to revise this state of affairs. Yet, in its approximately one hundred years of existence, psychoanalysis has had a tremendous influence on Western culture, and in spite of all the stones slung in its direction, it still has many supporters around the globe.

Nobel Laureate Sir Peter Medawar (1984) argues that certain, seemingly ‘naïve’ questions are beyond the power of pure science to answer, such as those concerning the purpose of human life. He believes that such ‘ultimate questions’, as well as psychoanalysis with its subject matter of ‘human nature’, belong to the ‘domain of myth’. Indeed it is important to note here that several physical scientists dismiss the social sciences in general as pseudoscientific.

Before assessing psychoanalysis against the criteria of pseudoscience, and for that matter, those of science, it is important to briefly consider what psychoanalysis is, and how it is assumed to work. The diffusion of Freudian theory is fascinating, it having been adopted for application in such fields as history, political science, literature, music and the arts. Further, for many laypersons Freudian theory is synonymous with psychology. Its goals are immensely ambitious, and theory and practice work hand-in-hand. Nevertheless, psychoanalysis is primarily grounded on pseudoscientific postulations that are inherently non-falsifiable.

Central to Freud’s theory is the division of the mind into three levels of consciousness, the first being the conscious. Below this rests the preconscious, which contains most of a person’s memories, and which in modern psychological language is equivalent to longterm memory. Below this lies the unconscious, which is one of the key concepts of psychoanalysis. According to Freud, this contains feelings, desires and memories that are repressed from the conscious because they are too traumatic or painful to deal with directly. One example of this putative repression is the Oedipus complex, which is concerned with incestuous desires. A further assumption of the unconscious is that the material in it is not available to the conscious mind, but nevertheless can powerfully affect behaviour – it therefore follows that repressed memories can result in psychological problems.

A major part of Freud’s theory deals with personality development, particularly from the perspective of sexual behaviour and sexual identity. Freudian theory is divided into four developmental psycho-sexual stages. In chronological order these are the oral, anal, phallic and genital stages. In some of these stages one has to resolve certain ‘complexes’ in order to develop normally. In Freud’s view, mature personality consists of the id, the ego and the superego, which all assume very different roles. The id is considered as the very core of personality, from which the other structures develop. The id is the most primitive structure, solely seeking to achieve pleasure and avoid pain. The superego can be thought of as the conscience of the person. These structures of personality bind together in a complex manner, and in individuals regarded as ‘normal’, they function in an interactive fashion.

Psychologist Terence Hines (1988) proposes several criteria by which a field may be judged as being either pseudoscientific or otherwise. One characteristic of pseudoscientific theories is that they exhibit non-falsifiable hypotheses. Some testable predictions can be derived from psychoanalysis, but they have typically been shown to be untrue. Several researchers, such as Hans Eysenck (1985), have embarked on the experimental study of Freudian concepts (see also Eysenck & Wilson, 1973). For instance, Paul Kline (1968) and Calvin Hall (1954) have empirically investigated the Freudian developmental assumption that toilet-training exerts a great influence on personality. This is based on a postulation that the mother’s training practices, together with her attitudes towards defecation, cleanliness, control and responsibility, strongly influence the personality development of the child. If this training is strict, then the child may take revenge upon authority figures by being messy, wasteful, extravagant, etc, or alternatively the child may become excessively neat and meticulous and develop a fear of dirt and exhibit overcontrolled behaviours. Hence, the theory can explain post hoc any extent of tidiness or messiness as resulting from strict toilet-training. According to Hall, this theory becomes twice non-falsifiable when the effects of gentle toilet-training are examined – these are indistinguishable from the result of strict toilet training, and once more, both personality styles can be explained post hoc, but neither can be predicted. In addition to the lack of clear logic in Freud’s postulation of the relationship between toilet-training and personality, studies investigating the relationship between these variables have found no relationship between the actual toilet training practices employed by parents and the child’s resultant personality style.

Related to these questionable assumptions of psychoanalysis are two equally questionable methods of investigating the alleged memories hidden in the unconscious: free association and the interpretation of dreams. Neither method is capable of scientific formulation or empirical testing. These methods bear no validity in reality. When these results are taken together with others, it seems plausible to suggest that falsifiability poses a problem for most aspects of psychoanalysis!

Daisie and Michael Radner (1982), ardent advocates of scientific methodology, observe that pseudoscientific proponents are inclined to “look for mysteries”. It could certainly be argued that Freud largely got away with a lack of scientific rigour in his work due to the volatile, obscure and often inaccessible content of the subject matter of psychoanalysis, especially as it relates to human sexuality. Whilst Richard Webster (1995), a radical psychologist, notes that much of Freud’s theory appears elegant and does display internal coherence, he argues that ‘laws’ of human nature are largely covered in mystery, and it is problematic to change this because, in order to investigate ‘human nature’, the power of science is not sufficient. Moreover, many of Freud’s achievements are seen to result from his own charismatic personality and “the heroic myth which he spun around himself during his own lifetime” (p. 9). Freud is sometimes likened to a religious, ‘messianic’ figure, who formed a ‘church’ and obtained a large crowd of followers, not because of the scientific basis of his teachings, but solely because of his authority.

Another of Hines’ (1988) observations was that pseudoscientists accuse sceptics of demanding more proof for their postulations in comparison to that required for more established theorists. But, as Hines puts it, “extraordinary claims demand extraordinary proof ” (p.5). Psychoanalysts often argue that clinical experiences are the proof for psychoanalytic theory and thus do not require evidence of the scientific kind, and these are the facts on which their ‘science’ is founded. However, since these data consist of symbolic interpretations of dreams, free associations, and such, in the light of this discussion such claims may be seen to be entirely circular in nature. Hines further notes that pseudoscientific proponents commonly fail to modify their theories in the light of new evidence. A notable example of this is the idea of motivated forgetting, also known as repression. Repression is said to be an active mechanism by which particular memories are prevented from reaching consciousness due to their emotionally painful content. Infantile amnesia, referring to the fact that adults usually have virtually no memories of their infancy, has widely been regarded as evidence for repression. In Freud’s explanation, this is because the period of early childhood is a time when the child is immersed in strong sexual desires, which are largely incestuous in nature. Because these desires cannot be satisfied, frustration follows. For a boy, his sexual feelings towards his mother may cause castration anxiety. Memories of these feelings are repressed when the Oedipus complex is resolved. Such memories cannot be allowed to enter the conscious mind, as there would be a risk that they would cause perversion and psychological damage. The scientific evidence for this notion of unconscious repression is lacking, as is any evidence that conscious thought or behaviour is influenced by repressed memories.

Infantile amnesia is regarded as a real phenomenon, but studies investigating memory and brain have shown that its causes are far from the psychoanalytical explanation. The currently accepted explanation is that infantile amnesia is due to the nature of the brain of the immature organism. A second important variable in childhood amnesia is the development of language, i.e., the limited language skills of young children make it more difficult to memorise information. However, a large body of evidence showing that infantile amnesia is not due to repression, but to the immaturity of the infant’s brain, has not made psychoanalysts revise the theory. Another example of a failure to update psychoanalytic theories is Freud’s field of psychohistory, created for understanding historic individuals. Several flaws in his theorising have been indicated, but again such theories have not been subsequently modified.

What is science, then? How scientific is psychoanalysis? According to Donald Spence (1987), an American psychiatrist, something deserves to be considered as a science when there is a prevalent regard for the data, which is available for all interested parties, and when theory is data-driven and changes in response to new observations. Further, the progress of the theory is cumulative and the original model may serve as a basis for newer models. Finally, the claims are based on evidence rather than on authority. In this view science is immensely democratic. In terms of the above criteria, psychoanalysis fails on every count. Frank Sulloway (1979), a psychologist and historian of science, has actually described psychoanalysis as “a scientific fairytale”. However, the subject matter of psychoanalysis, human sexuality and human nature, are laden with powerful taboos. Webster (1995) argues that to postulate theories concerning such issues requires not only intellect, but also emotional lucidity, something that is not commonly regarded as a characteristic of the scientific mind. Furthermore, to engage in such an activity requires a pinch of rebelliousness, which again is a quality rarely seen amongst those trained in natural sciences. In Webster’s view, scientific ideas should not be judged by their intellectual source but by their explanatory power.

It cannot be denied, however, that Freud’s theory is superlatively ingenious, creative and perceptive. It further provides an initially plausible explanation of many aspects of human sexual behaviour. To dismiss psychoanalysis as being without any intellectual merit or importance would be wrong, and to do so would dismiss all of the many respectable authors who ever wrote in the psychoanalytic tradition.

The majority of psychologists hold that psychoanalysis is a pseudoscience, but perhaps the very business of examining Freud’s work from the scientific perspective is unnecessarily harsh. Hans Eysenck, a hard-core behaviourist and iconoclast of the twentieth century, maintains that for many, Freud’s contribution has not been to the scientific study of human behaviour, but to the interpretation and meaning of mental events. Specifically, Freud pioneered the desire to understand those individuals whose behaviour and thinking cross the bounds of convention dictated by civilization and cultures. It is difficult to dismiss the importance of psychoanalysis as it is so tightly entangled with our cultural history. However, perhaps the most transparent evidence that Freud was wrong is that he is very difficult for us to understand, and much of him remains an enigma – in Webster’s (1995, p. 29) words, “a psychologist who is beyond the reach of psychology, the creator of a movement which has encircled the globe but which has formulated no theory which can even begin to account for its own success”. It seems clear to me that psychoanalysis belongs to the ‘domain of myth’, and while of course myths may be enigmatic, they are not in the least scientific.

References

- Eysenck, H. J. (1985). Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

- Eysenck, H. J., & Wilson, G. D. (1973). The Experimental Study of Freudian Theories. London: Methuen.

- Hall, C. S. (1954). A Primer of Freudian Psychology. Cleveland: World Publishing Co.

- Hines, T. (1988). Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books.

- Kline, P. (1968). Obsessional Traits, Obsessional Symptoms and Anal Erotism. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 41, 299–305.

- Medawar, P. B. (1984). The Limits of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Radner, D., & Radner, M. (1982). Science and Unreason. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Spence, D. P. (1987). The Freudian Metaphor. New York: Norton.

- Sulloway, F.J. (1979). Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend. London: Burnett Books/André Deutsch.

- Webster, R. (1995). Why Freud was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis. London: HarperCollins.