I’ve been doing this ‘skeptical dentist’ thing for a while now. Before writing for The Skeptic, I was part of the dental panel at QEDCon in 2016 and co-hosted an ‘evidence-based everything’ (currently on hiatus) podcast. So it may come as a surprise to you to hear that I’m a qualified dental acupuncturist.

If you’re still reading, I’ll explain how and why.

As I’m sure you’re aware, acupuncture is the insertion of thin needles into specific points of the body and is a crucial component of traditional Chinese medicine. (TCM) Research has repeatedly shown it to be clinically ineffective. It is pseudoscience. So why would I spend my own time and money learning about it?

Firstly, although I’ve been a dentist for nearly 20 years, I’m terrified of needles. It’s much easier being on the dentist end of a syringe, and I’ll do pretty much anything to avoid being jabbed. I correctly assumed that an acupuncture course is going to involve having needles inserted into you. I also thought that this might help me overcome my fear. It didn’t.

More importantly, though, I wanted to understand what drives people into becoming alternative practitioners and the kind of training they go through to get there. If we want to appreciate what makes practitioners tick, we need to know how they’re taught to think. And what better way to do that than to become one. Fortunately, I found a course that was close by and inexpensive. So, a few years ago, I turned up at a local practice on a cold January morning to have needles repeatedly thrust into me.

The delegates had a bit of a meet and greet to kick things off as usual with these things. The world of dentistry is a small one, and everyone knew at least three other people on the course. Our lecturer for the day turned out to be one of the friendliest dentists you could wish to meet. Interestingly, they also dabbled in a bit of magic and worked with children and disabled patients.

The introduction to acupuncture touched on the TCM idea of meridians, those mysterious invisible paths of qi energy running through the body, and the ‘Western’ concept of gate control theory. Acupuncture, we’re told, is particularly effective for patients with anxiety surrounding dental treatment. It can dull down the gag reflex and help with jaw problems. This preamble was admittedly light, without any skeptical investigation of the evidence, which is perhaps unsurprising. If you’re on a course to learn acupuncture, you already know it works, right?

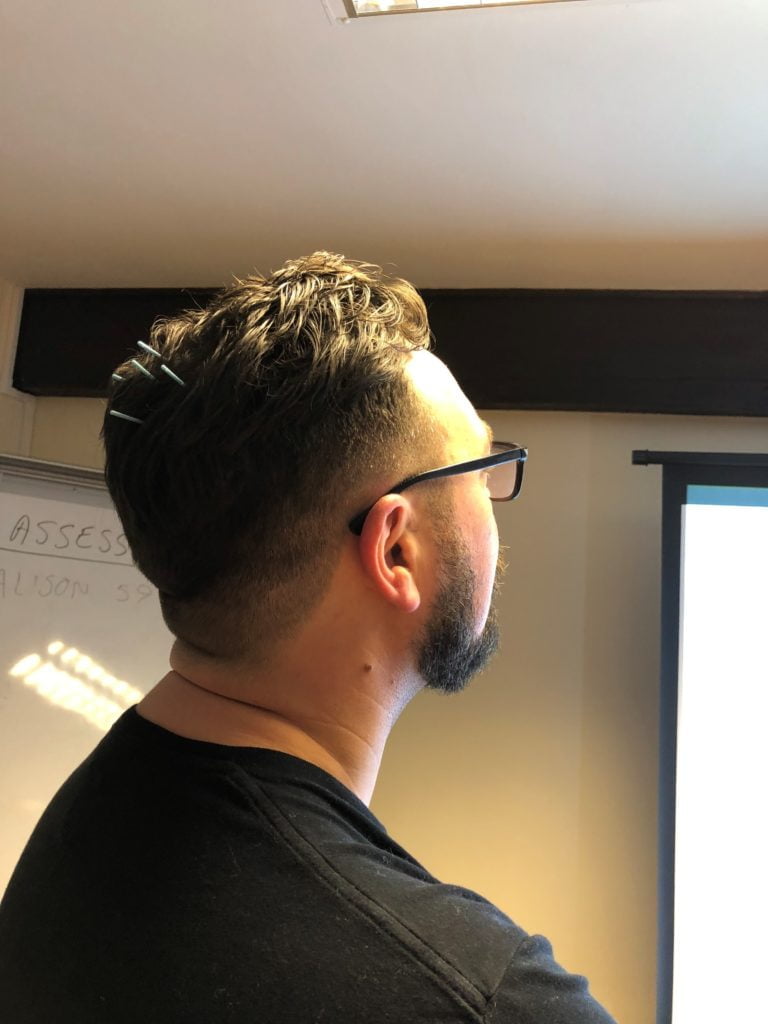

Without much further ado, our tutor hands out a variety of needles; we partner up and are let loose on each other. To say that I was nervous about this would be an understatement. Our first effort involves us drawing lines on our hands and inserting needles where they intersect. Despite my concerns, this was surprisingly pain-free.

Within the next few hours, I had inserted needles into various areas of other delegates’ scalps and faces and had the same done to me. I came away from the day with a certificate, a stock of needles and the assurance that I was now able to go ahead and do this on patients.

It probably won’t surprise you to hear that those needles are still in my surgery drawer, unused. The course didn’t convince me that I should be using acupuncture in my clinical practice, but that’s not to say I didn’t learn anything from it.

When we’re looking after patients, we’re using more than just our clinical skills. Within dentistry, especially, there’s a whole raft of other abilities we need to use to make patients feel relaxed and trust us. Quite frankly, most of our patients would rather be anywhere else than in our chair having treatment done, so anything we can do to make their lives easier is beneficial. Not just for our patients but for us as well.

We know that one of the reasons patients feel a benefit from many forms of alternative medicine is because of the often-extended consultation process, where practitioners will often dig into the social and psychological reasons for their visit. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that our course tutor worked mainly with disabled patients and children. These patients are the ones that often need the most careful coaxing into accepting treatment. The skills required to do this are often lacking in medical professionals, overlooked in undergraduate training and often ignored when considering future professional development.

Believe it or not, empathising with the people who present to us for treatment doesn’t always come naturally to medical professionals. We’re taught to diagnose, prescribe, and treat, but we’re not taught how to build a relationship with a patient.

But it’s the ability to create those relationships that the acupuncturists, homoeopaths, and other alternative practitioners are often particularly good at, and it is something we can all learn from. While we shouldn’t be learning how to practice medicine or dentistry from alternative practitioners, there may be something to learn from them.

Dental acupuncture is supposed to be particularly good at relieving anxiety around treatment and various types of muscular related pain. These are complex psycho-social issues that are often difficult to treat with physical interventions. It’s here where our non-clinical skills excel and where the benefits (and I use that term in the loosest of all possible senses) of alternative medical practices lie.

So although I didn’t learn a tremendous amount about acupuncture as a clinical intervention, and I certainly wouldn’t recommend it to anyone, I learned a considerable amount about how to approach patients, how to get them on my side and how to make treating them easier for everyone. And that’s invaluable.

Now, who’s going to chip in for my training as a homoeopath?