For a country which is constitutionally secular, the USA suffers frequent outbreaks of fervent religiosity.

Parts of the country were founded with the desire to practice rigorous forms of Protestantism. The nineteenth century saw ‘The Second Great Awakening’. You’ve seen films with gatherings in tents, charismatic preachers and emotional congregants? Well, this was that. The very real physical dangers that people faced on the frontiers translated into a sense of moral peril, and charismatic religiosity provided a coping strategy.

Religious revivals continued into the twentieth century. Evangelical preachers like Billy Graham and movements like the Southern Baptists thrived.

The counter-culture of the 1960s experimented with traditional and conservative approaches to religiosity and social relationships. Although the liberalisation that sprang from this era was ultimately long-lasting, the acute utopian phase faltered in a series of ugly scenes. The hippies of Haight-Ashbury went from the Summer-of-Love psychedelics to heroin addiction and street drug-wars. The notion of an ideal, shared, communal life took a hit after the grotesque murder of Sharon Tate and four others by the Manson ‘family’ in 1969. The civil rights movement, which had started with dauntless, peaceful protesters like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King now altered to accommodate more forceful tacticians like Malcolm X and the Black Panthers.

The process of urban decay which had started in the ‘50s became hideously manifest in the ‘70s. In 1975 New York City nearly went bankrupt. The 24-hour NYC blackout of 1977 hosted an unprecedented looting spree. The Fire and Police unions called it ‘fear city’. In ‘The Bronx is Burning’ Jonathan Mahler wrote:

“The clinical term for it, fiscal crisis, didn’t approach the raw reality. Spiritual crisis was more like it”.

If you were there at the time, pessimistic and prone to labelling trends, it could have seemed that 50s stability had metamorphosed into disorder and uncertainty, stopping only briefly at Utopia along the way. ‘Bewitched’ ran on TV from 1964-72 and endorsed the old ways, with its main character attempting to live a traditional housewife role – ‘I Love Lucy’ with spells. The soporific effect of suburban conformity was comically upset each week by the antics of the under-cover sorceress and her interfering magical mother.

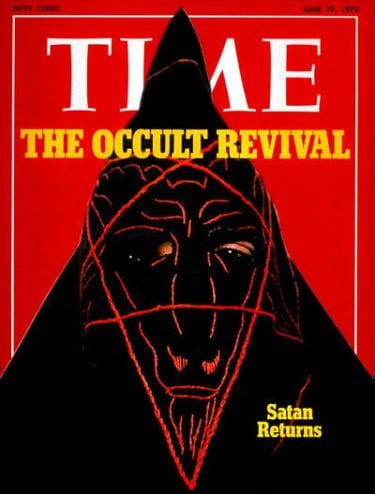

But the tone changed as Satan entered the room. ‘Rosemary’s Baby’, was published as a book in 1967 and made into a film in 1968. A young woman’s pregnancy and whole life is subsumed by the organised witch-coven in her apartment building. William Peter Blatty wrote ‘The Exorcist’ in 1971 and the movie followed two years later. ‘The Exorcist’ is notable for its reactionary conservatism: demonic forces make their way into the world via a Ouija board (very popular at the time) and the only solution is to turn to the one valid authority, the Catholic Church.

If ‘Bewitched’ was magic trying to conform to suburbia, ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ and ‘The Exorcist’ was magic trying to subvert it, a more paranoid take.

Cognitive and neuro-psychologies remained to be established. Freudian psychology, with its notions of repressed memories and urges prevailed. Perhaps that was why a 1973 book (also later adapted into a two TV films) called ‘Sibyl’ was received so uncritically. The alleged childhood abuse of the pseudonymous ‘Sybil’ was ‘uncovered’ by her psychiatrist, and multiple-personality-disorder (later called dissociative-identity-disorder) was diagnosed. In the same vein the 1980 book ‘Michelle Remembers’ ran much of the same track with the addition that the abuse was organised and Satanic. Modern psychology does not accept the notion of recovered memories uncritically any more. You’d be lucky to get it taken seriously/unopposed in court, for example. The existence of dissociative-identity-disorder is similarly contentious now. In this respect, we can sympathise with people fifty years ago who were reading the ‘science’ of their day rather than ours.

But there were elements of these cases, even at the time, which should have made anybody queasy. The relationships between the therapists and the patients were not formal: Cornelia Wilbur and ‘Sybil’ (later revealed as Shirley Mason) were co-dependently entwined (as highlighted in ‘Sybil Exposed’, by Debbie Nathan). ‘Michelle’ eventually married her therapist and the book’s author, Lawrence Pazder. Both books were co-written/co-owned by the patients; their stories were part therapeutic process, part business enterprise.

New Religious Movements, and cults

One person’s ‘New Religious Movement’ is another person’s ‘cult’, and there was no shortage of either. I remember a moral panic about the ‘Moonies’, although Jim Jones’ ‘The Peoples Temple’ ultimately proved to be more destructive (and theatrically so) with a mass suicide in Guyana in 1978.

Perspectives on the occult and new-spirituality bifurcated. NRMs were viewed askance by conventional religious types (who seemed to forget that their own institutionalised religions had all been new at some point). Esoteric types thought of it as valid spirituality and self-realisation. I can’t be the first person to have detected a bit of narcissism in high levels of preoccupation with self-transformation. It endures today, of course, in the form of self-help books which are still so plentiful that they justify their own section in the bookshop.

Neo-pagans and Wiccans, influenced by Margaret Murray, were the first people to self-label as ‘witches’. In the early twentieth century, Murray influentially developed and promoted the ‘witch-cult hypothesis’. It proposed that a pagan religion survived Europe’s conversion to Christianity, and that the widespread witch trials of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were an attempt to finally extinguish it. If only she had stuck to her actual area of expertise – Egyptology.

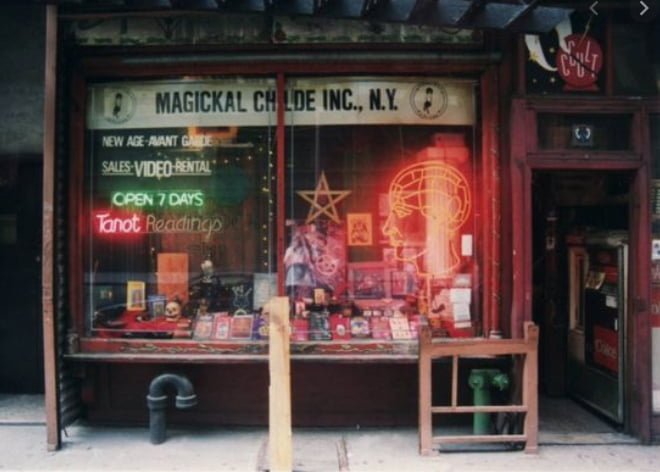

In centuries past, the label ‘witch’ had been strictly bestowed from outside, and was certainly not one you’d want to attract. The border between the occult and New Age bookshops was indistinct, although I’d put Magickal Childe on West 19th St., where I spent many an hour browsing through Strange Books, well to the occult side of that divide. Even fantasy games like Dungeons and Dragons were viewed as morally hazardous by some by the ‘80s.

70’s dystopia seemed to reach a peak with the Son of Sam murders. Before he was caught, Berkowitz conducted a public correspondence with Pulitzer-winning New York Post columnist Jimmy Breslin of whom former FBI agent Robert K. Ressler said:

(He) baited Berkowitz and irresponsibly contributed to the continuation of his murders. Rupert Murdoch had acquired the New York Post in 1975 and can hardly have been displeased by the sales which followed such sensationalist journalism.

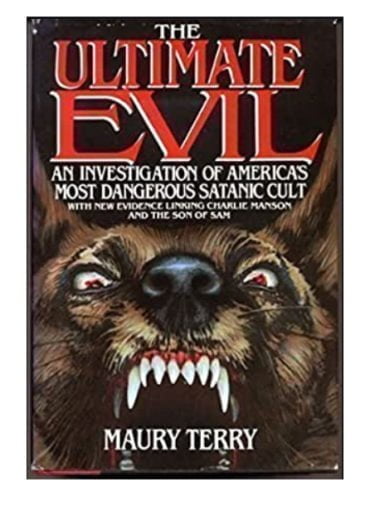

In 1987, a book was published which made a deep impression on me and, to judge by the reverberations for the next few years, many parts of the US media too. ‘The Ultimate Evil’ by Maury Terry proposed that Berkowitz had not acted alone but as part of an organised group of Satanists called ‘The Children’. Among those alleged conspirators were the brothers who lived across from the back of his apartment building, John and Michael Carr, whose family dog Berkowitz had shot. Just like all conspiracy theory books, it is incredibly pleasing to read. It fits together so beautifully … just in the way that real life doesn’t.

Terry left his papers to Joshua Zeman who has made a documentary ‘The Sons of Sam: A Descent into Darkness’ which is airing on Netflix at the moment. This heir of Terry’s monomania is too polite to call him out directly, but there is enough there for skeptics to see that we are looking at the life’s work of a man who was utterly fixated, a man who had the solution before he had the evidence.

Maury Terry was described as an investigate journalist, a charitable title for the editor of IBM’s in-house magazine. He later attracted a salary from media giant corporation Gannett Newspapers. As a former colleague says in the documentary:

He had a golden shovel that allowed him to dig as much as he wanted … there was always another layer.

Satanic abuse as sideshow spectacle

Geraldo Rivera produced and hosted lurid talk shows at the time. Among his ‘cannibalism’ and ‘reverse speech in Rock’n’Roll music’ specials, his 1988 ‘Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground’ episode featured Maury Terry as a guest.

Terry also managed to interview Berkowitz himself on camera in 1993 and 1997. The questioning is comically leading. Berkowitz ‘admitted’ that he had been in league with the Carr brothers (who had been unsubtly suggested by Terry, and who were by then too dead to sue) and then refused to name any others. Terry took this is a sign that the Satanists were still powerful and that, even in jail, Berkowitz was afraid.

The blessings of the ‘80s included pink lycra and big hair. But it was a while before the money filtered through to ordinary people. We weren’t all yuppies. In this economy, a family couldn’t prosper on one salary: women with children started working full-time, which meant that they became reliant on child-care in a way that previous generations weren’t.

The day-care abuse hysteria has been well-documented. It mostly happened in the USA, but there were manifestations in the UK, such as the Cleveland Child Abuse scandal of 1987. In retrospect they’re as bizarre as the twelfth century deaths of William of Norwich, Harold of Gloucester, Robert of Bury and Hugh of Lincoln which were claimed at the time to have been perpetrated by the Jewish communities near their homes in the medieval Jewish blood libel accusations.

By the nineties the tide was turning. A 1992 Department of Justice published a report for investigators written by Kenneth Lanning, a Supervisory Special Agent with the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit in Quantico, Virginia. It debunked claims of systemic ritualistic occult abuse in America.

“If something wasn’t happening, why do so many intelligent, well-educated professionals believe it is?” Lanning asked himself. He concluded that:

Regardless of intelligence and education, and often despite common sense and evidence to the contrary, adults tend to believe what they want or need to believe; the greater the need, the greater the tendency.

The path leading to the Satanic Panic of the ‘80s was long and involved the creation of many dubious experts. Some USA law enforcement agencies provided training to help recognise ‘Ritual Satanic Abuse’ but, of course, just because there is a course about it, doesn’t mean it’s real. Similarly, Pazder (‘Michelle Remembers’) & Wilbur (‘Sybil’) were both regarded as experts in the field of recovered memories.

It seems that sometimes we don’t actually need a Satan. Well-meaning, deluded and fervent people will do His work for Him.