I never used to care for cats – until recently when my flatmates brought home a kitten, Finn. He was sweet and playful with piercing green eyes, he could knock over a prized mug and still look adorable in the process. I was instantly hooked. I would take tens of pictures of him in cute poses and adopted that jarring squeaky voice whenever he did something mildly cute. I had become a crazy cat lady!

Though this newfound love is annoying to those who don’t share my new affection for cats, it can be put down by most as relatively tame and disconcerting behaviour. However the reason behind this new affinity – of mine and many others – may be due to more than just a cat’s cute looks. A recent more sinister explanation of this behaviour has been brought into mainstream attention via a TED talk with the title, Is there a disease that makes us love cats? (De Roode, 2011).

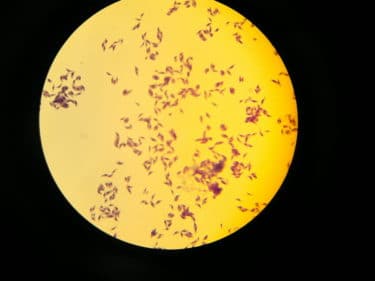

While the title of the presentation sounds automatically sceptical, the talk itself speaks at great lengths of the impact of toxoplasmosis, a parasitic infection that lives in the human brain and is allegedly capable of manipulating our behaviours to make us love cats. Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by the parasite toxoplasma gondii. T gondii is unusual in that most mammals and birds can be infected with the parasite, however it can only reproduce sexually in the intestines of cats.

For T gondii to complete its lifecycle, a sinister side of the bacterium presents itself. It is known to manipulate the behaviour of its host, normally rats and mice, by overriding their innate fear of cats to bring the poor rodents closer to their impending doom (Dubey, 2016).

Humans come into contact with the infection when changing the cat litter tray; it can be caught via the shedding in the cat’s faeces.

Once a person has been infected with T gondii, they remain infected for life, as the parasite often remains dormant, but ‘hidden’ from the immune response. While humans are not the intended host for T gondii they can allegedly be subject to the parasite’s mind-bending influences. Not only does toxoplasmosis apparently make us love cats, the TED talk also mentions studies that suggest infected humans have higher occurrences of slowed reactions, less concentration, obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Torrey et al., 2015).

The thought is terrifying – but how does this relate to me and Finn? Are we both infected? How could such nasty debilitating mental health disorders be caused by the humble and once innocent-looking cat? Following from the TED talk, many others have surfaced and added fuel to the fire. While a minority were well referenced and subject to rigorous scientific testing (Webster, 2001), most were sensationalist fear-mongering articles with titles such as, ‘‘Cat lady’ parasite linked to brain damage, How your cat is making you crazy’ and a Daily Mail article referencing, “a mind controlling feline parasite”. Articles on the topic have collectively massed over a thousand shares and hundreds of comments. The search for toxoplasmosis spiked on Google after the TED talk’s release due to the paranoia invoked by simply owning and being near cats.

So what is to be done? While nothing stated in the TED article is technically wrong, it heavily suggests severe mental health concerns related to toxoplasmosis infection in humans. This encourages the reader to believe their cat could be responsible for more than just the accumulation of cat hairs everywhere, but also for a worrying range of mental health issues. The study cited in the Daily Mail article states that half of the people who had a cat as a child were then diagnosed with mental illnesses later in life – a slightly larger percentage than those who didn’t grow up with a cat.

The study cannot prove that the parasite can cause mental illness; it simply hypothesises that it might cause mental illness based on a loose, seemingly random link between having a cat in childhood, and later developing mental illness. The study here doesn’t even mention toxoplasmosis. The article wrongly presented a small scale and mostly irrelevant piece of research as robust scientific evidence for mind controlling parasites! Definitive conclusions on the effect of cat ownership surely await human trials, peer review and replication of research. To prove that a link between altogether random and unrelated variables can be found, fivethirtyeight.com collected large amounts of data on many seemingly meaningless variables, and proved that through p-hacking*, they were able to find statistically significant correlations for random statements such as “having an inny belly button” and “liking red cabbage”. This proves rather elegantly, that just because something may be statistically significant it doesn’t necessarily mean that it is true! It illustrates that just because you have a cat and act a little crazy sometimes, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the cat is causing it.

While we come to expect shoddy journalism from sources like the tabloid press, wouldn’t we hope that TED might be better? The TED talk illustrates part of the argument with an example of rats’ erratic behaviour following toxoplasmosis infection. While correct in asserting that laboratory evidence has shown infected rodents are more reckless around cats (Stibbs, 1985), this assertion is not proven in humans. This lone study’s applicability to humans is limited, and the talk is in error to imply so. The behavioural effects of toxoplasmosis in humans, if any, are subtle and hard to distinguish from the array of many other irrational human behaviours.

The results of the experiments listed in the TED talk as well as other sensationalist articles do not measure up to the claims and effect boasted. Nuance and tentative findings often get blown out of proportion by news outlets to get clicks and sell papers, all at the expense of our four-legged friends. This demonstrates how we can be easily deceived, especially when it is a scientist who is making the claim.

Not only has behavioural manipulation by the parasite been debunked, it’s also very rare to catch toxoplasmosis from cats either – they have wrongly been named the sole culprit of spreading T gondii and toxoplasmosis infections. Although it must be noted that cats are important in the life cycle of T gondii infections, human infections are often more likely the result of ingestion of undercooked meat containing the parasite, or contaminated water. It is estimated that worldwide more than 500 million people are infected with T gondii (Bowie, 1997). Those that do carry the infection often carry no symptoms, the infection only has negative implications for the small percentage with weaker immune systems (Frenkel et al., 1972).

Stronger evidence exists for the effect of suggestibility; much like horoscopes, as many of the symptoms explained in the TED talk and other articles such as slowed reactions and lowered concentration apply to many, leading people to believe that they are infected when this is not actually the case. By using these generalised sweeping Barnum statements, these outlets were able to provide subjective validation in which the reader is able to find personal meaning in the statements of loved-up cat behaviours that, in reality, apply to many people, giving the articles false plausibility. This raises the issue with TED talks in general, as several talks and presentations have since been found to be incorrect in places and have needed to be updated.

Despite a scientific background, some speakers subscribe to sensationalism and hyperbole, and get away with it largely due to their credible scientific brand or credentials. Quality scientific research can be oversimplified to the degree that the audience gets misinformed. Sloppy journalism can cause fear-mongering, and encourage other media outlets to follow suit in producing articles that challenged the safety of the company of our feline friends.

Research conducted by Kahneman in 2002 suggests that we have two brain systems, one that functions via intuition that responds more quickly to emotional stimuli, compared to the second reasoning system. The first pathway is seemingly being exploited here: media outlets are successfully able to harness fear and emotionally charged wording to gain attention to bring readers to their content – though arguably the fault is somewhat with the lay public too, who choose to consume these stories. We need healthy scepticism to distinguish the good from the bad.

So where does the answer lie? Do we trust these articles wholeheartedly and stick to fawning over dogs and banish cats from our homes and affections? Thankfully, the future for cat lovers is not this hopeless. While it is true cats are capable of contributing to the spread of toxoplasmosis, the likelihood of this happening is blown vastly out of proportion. Uncooked meat and tainted water supply are the main culprits.

Even if a cat were to infect someone, the effects of the infection are slight and no research points strongly towards mind-controlling, cat-fawning behaviours. While we can’t yet rule it out completely, more clinical research is necessary before we start barricading the cat flap.

The responsibility lies with TED as well as other media outlets who should make more effort to be clearer about the validity of their sources, and steer away from emotional sensationalism and lazy journalism just to get clicks. After all, the impact of misleading and false statements is wide-reaching.

Though it must be stated that some responsibility is with the lay audience themselves; we must strive for better journalistic integrity and fight the urge to give into clickbait. If it sounds too good to be true, it’s probably bullsh*t.

Lastly, cat owners surely share some of the blame. They ought to be more sympathetic to those that don’t admire cats, and maybe if their behaviour didn’t seem so crazy, people wouldn’t believe that a mind controlling parasite could plausibly be the cause of their loved-up cat behaviours!

References

- Bowie, W. R., King, A. S., Werker, D. H., Isaac-Renton, J. L., Bell, A., Eng, S. B., & Marion, S. A. (1997). Outbreak of toxoplasmosis associated with municipal drinking water. The Lancet, 350(9072), 173-177.

- Dubey, J. P. (2016). Toxoplasmosis of animals and humans. CRC press.

- Frenkel, J. K., & Dubey, J. P. (1972). Toxoplasmosis and its prevention in cats and man. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 126(6), 664-673.

- Gray R. (June 2015) “Is your CAT making your child stupid? Mind-controlling feline parasite is linked to poor memory and reading skills”. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3105707/Is-CAT-making-child-stupid-Mind-controlling-feline-parasite-linked-poor-memory-reading-skills.html#ixzz4Qy3qVImQ

- Kahneman, D., & Frederick, S. (2002). Representativeness revisited: Attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment, 49.

- De Roode J. (2011). Retrieved from http://ed.ted.com/lessons/is-there-a-disease-that-makes-us-love-cats-jaap-de-roode

- Torrey, E. Fuller, Wendy Simmons, and Robert H. Yolken. “Is childhood cat ownership a risk factor for schizophrenia later in life?.” Schizophrenia research 165.1 (2015): 1-2.

- Webster, J. P. (2001). Rats, cats, people and parasites: the impact of latent toxoplasmosis on behaviour. Microbes and infection, 3(12), 1037-1045.

This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 26, Number 3