As we reach the end of what has been an undeniably intense year, we can take some comfort from the knowledge that the world looks likely to receive the Christmas present we’ve all wanted most: a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine. And while the majority of readers in the UK will have to wait a few more months to receive their present (and readers in some other parts of the world may have to wait even longer, given the way in which wealthier nations have bought their way to the front of the vaccine queue), the knowledge that there is light at the end of the 2020 tunnel should give us all some much-needed hope.

However, it would be naïve to plan for 2021 to be entirely smooth sailing through a world of renewed reason and appreciation for scientific progress. While the prevailing pseudoscience of 2020 concerned the causes of Covid and the ways in which society should mitigate and manage the effects of the pandemic, 2021 will undoubtedly see a committed and vocal anti-vaccine movement. In fact, we’ve already seen the foundations of that movement, with conspiracy theorists making fanciful allegations regarding Bill Gates and encouraging people to go without masks, in spite of the overwhelming evidence of their efficacy. Those same voices will be heard next year, shouting loudest against the vaccine.

With an anti-vaxx movement in the ascendency, skeptics and science communicators look set to have their hands full as we start the new year, pushing back on vaccine misinformation and encouraging the hesitant to line up and get vaccinated. If we want to be as effective as possible in countering the misleading rhetoric of the anti-vaxxers, it’s important that we first of all understand the arguments we want to diffuse, and understand those who spread them.

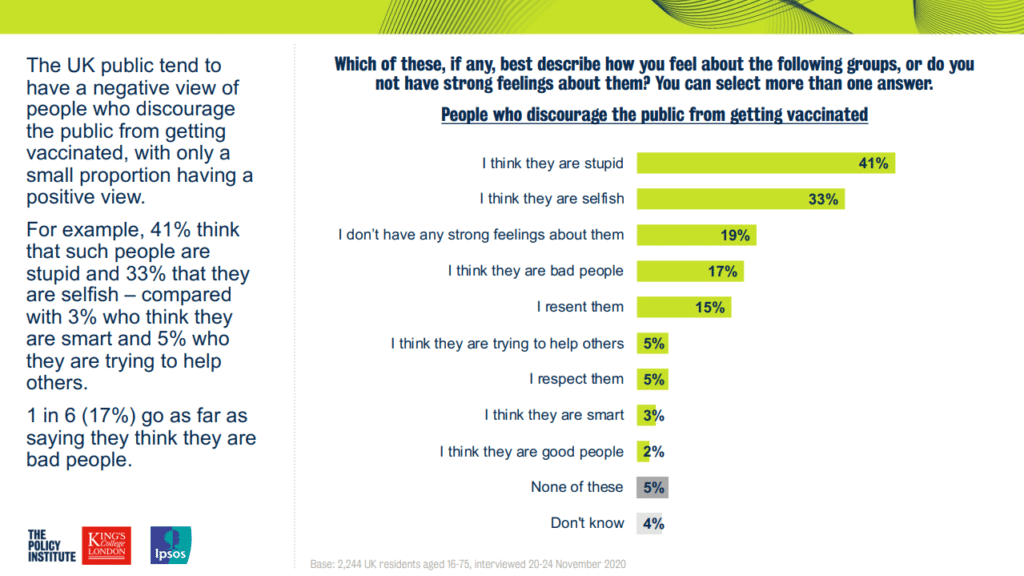

With that in mind, a pair of recent Ipsos Mori opinion polls, conducted on behalf of The Policy Institute at Kings College London, make for interesting reading (and for those who have seen me write or lecture in the past about opinion polls and survey methodology, I’ll offer some assurances that these look to be well-conducted). The first, published December 10th, looks at the way in which the British public views vaccines, and the way in which we view anti-vaxxers. The most eye-catching take-home from the poll, and the one which generated the most headlines, came when survey respondents were asked to express their opinion of “people who discourage the public from getting vaccinated”, where they were asked to select their opinion from a list of pre-written options.

According to the results of the poll, 41% of people believe that anti-vaxxers are stupid, 33% think they are selfish, and 17% think anti-vaxxers are bad people. Conversely, very few people had favourable views of anti-vaxxers, with just 5% of people respecting them, 5% believing anti-vaxxers are trying to help people, 3% thinking they are smart and 2% thinking they are good people.

When it comes to people who promote vaccination, respondents to the survey were fairly positive, albeit somewhat mutedly: 43% of respondents thought those who encourage the public to get vaccinated are trying to help others, 29% respect them, 27% think they are good people and 23% think they are smart. It would have been nice for one of those categories to tip over the 50% mark to show a majority of support, but it’s possible that the positive support was diluted across multiple favourable responses. Notably, only 2-3% of people expressed any negative opinion about those who promote vaccines.

Personally, I have slightly mixed feelings about these findings. On the one hand, it’s obviously enormously encouraging to see anti-vaccine sentiment faring so poorly, with such widespread mistrust of people who discourage vaccines. The fact that we can go into 2021 with some cautious optimism that the dissenting voices on vaccination are likely to be in the minority is far better than the impression given by the weekly gatherings of Covid-deniers we’ve seen in cities across the country these last few months. At the very least, we should take some comfort from the fact that we are not likely to be facing an uphill battle to persuade people to be vaccinated (even if the country ends up navigating some complicated logistics to get the vaccines into the country via our post-Brexit ports).

On the other hand, the view that the pro-vaccine respondents to the Ipsos Mori poll, and that those who commented on the coverage of the poll on social media, had of anti-vaxxers leaves me somewhat uneasy. It can be comforting to write off anti-vaxxers as ‘stupid’ and ‘selfish’ and ‘bad people’, especially when their actions jeopardise the health and wellbeing of vulnerable groups of people, but is that a fair reflection of who we are actually disagreeing with? I’m not convinced it is.

In my experience of talking to people who hold views outside of the mainstream – including views that are outright damaging and dangerous – the answer is rarely that they are unintelligent, or uncaring, or that they house deliberate ill intent for the rest of society. Instead, I’ve found that they are often people who sincerely believe what they’re doing is correct, and that they’re trying to protect people from what they see as being certain harm. That they’re entirely mistaken about that harm – and that they’re often advocating for actions that would be outright dangerous – doesn’t change their intentions or their beliefs.

If I had been part of Ipsos Mori’s poll, I genuinely don’t know what I would have answered when asked which of the responses best fit my opinion of anti-vaxxers. Do I think they’re bad people? On the whole, probably not. They’re certainly doing something bad, but some of them might actually be good people (whatever that means) – just, good people who are very wrong about this issue. Do I think they’re selfish? Almost certainly not – by and large I think they think they are trying to help people… they just have the wrong information and have all the wrong answers.

Do I think they are stupid? I’m not entirely sure that’s a relevant question – being right or wrong on something you feel strongly emotional about is rarely an issue of intelligence. Very smart people can be exceptionally wrong about something, where they have an emotional or ideological blind spot. Indeed, very smart people are very good at being exceptionally wrong, because they are very good at finding justifications for their wrong beliefs – they have to be, because they have to be able to justify their position to themselves, and after all, they’re very smart.

This may all seem like achingly-worthy hand-wringing and hair-splitting, but I genuinely think this matters, because the way we think about and talk about the people we disagree with colours the way we disagree with them. If we see anti-vaxxers as unintelligent, selfish, and even evil, it’s easy to write them off as being beyond reach or beneath us – neither of which are useful starting points for an effective counter to their rhetoric.

Instead, if we try to understand the values, fears and motivations which drive people into anti-vaxx positions, we might be better equipped to dismantle those arguments. If we understand that some people’s anti-vaxx belief stems from fear about the speed of the development of the vaccine, and their worries that vital safety steps might have been missed, we can talk about the ways in which vaccines are tested and the reasons why we should have confidence in these particular vaccines.

If we understand that some people in the anti-vaccine movement are motivated by a misguided desire to protect people and protect their children, we can demonstrate that we understand and appreciate that desire, and that we share in that goal, and we can talk honestly about the reasons why we can believe this vaccine is worth getting.

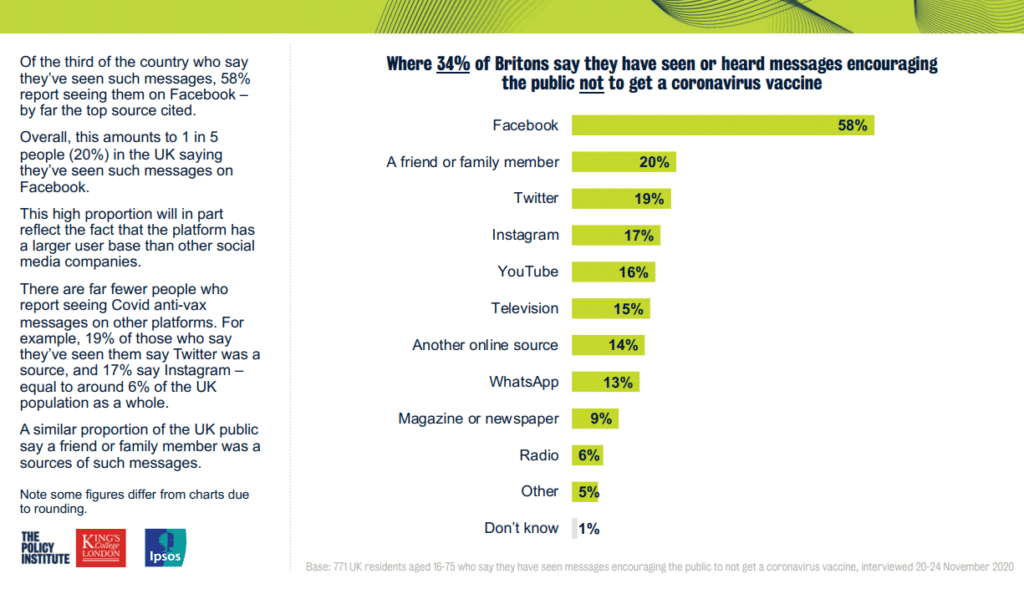

If we recognise that not all anti-vaxxers are fully committed in that belief, we can offer reassurance rather than condemnation, to let the vaccine-hesitant know that asking questions is completely reasonable, but that the key is knowing where to look for answers that can be trusted. We can explain why social media is not a good place to look for those answers, and why it’s so important to question the answers they feel most emotionally driven to accept. That’s particularly important, given that the second Ipsos Mori poll found that social media – and Facebook in particular – is by far the most common place where people are likely to encounter vaccine misinformation. We can write anti-vaxxers off as being a lost cause or as being too stupid to bother with, or we can choose to be a voice that offers calm, polite, approachable and reasonable opposition to that misinformation.

The COVID-19 vaccine is here, and that’s a relief. The anti-vaccine movement is here, too; small, but vocal – and there is no denying that it presents a challenge… but it also presents an opportunity for skeptics and science communicators to make a difference. We will only be able to do that effectively if we engage with those who might be unsure, and if we listen to fears rather than assign them straw-man motivations that let us dismiss them as evil, selfish and stupid.

It’s true that not all anti-vaxxers will be reachable, but if we start from the assumption that they’re not all beyond reach, we’ll have far more chance of encouraging people to see reason.