Your sick aunt has started seeing a crystal healer. Your best friend announces in the pub that he’s very suspicious about all this 5G business. An old classmate has announced on Facebook that they’re not going to vaccinate their kids. We’ve all been in these kind of arguments before. But what’s the best way to have a good conversation with someone with unconventional, dangerous or irrational beliefs, and still get the invite to tea and cakes with Aunt Mildred once the hellscape of 2020 is over?

Like many of us, I’m frustratingly prone to getting into bad arguments for bad reasons, so I have delved into what the evidence tells us about having better arguments.

Why Are We Arguing in the First Place?

In today’s polarised world it probably needs to be said: be nice. Anyone who is worth your time arguing with is presumably someone you care for, after all. More importantly, being reasonable with people is likely to yield better results. People are unlikely to respond to attacks on their beliefs, their values, and their self-integrity, which create a stress response and cause people to react defensively – not a good atmosphere for changing minds. Experiments on self-affirmation theory suggest that affirmation makes people more likely to be open-minded.

Most parents will have found themselves in a scary conversation with another parent who they are surprised or shocked to discover is anti-vaccination. Attacking them as a bad parent also attacks their self-integrity – their belief that they are a good parent, who cares for children’s safety and wellbeing – and is not the best start to a better conversation about vaccines.

(Side note to other parents: return your children’s flu vaccination permission slip, promptly!).

If the debate is with an acquaintance or colleague, we’re out to make friends and win converts, not destroy our enemies. We’ve all seen debates in which sharp and famous skeptics eviscerated their opponents on stage. Whether you’re an ardent fan of the late Christopher Hitchens or were troubled by his views on the war in Iraq (or a bit of both) it should go without saying that you are not Christopher Hitchens, who was up on stage as a professional debater, not trying to convince his friend, colleague, beloved aunt or even a random somebody on the internet to abandon their attachment to crystal healing rather than chemotherapy.

Undoubtedly such debaters believe passionately in what they’re saying, but they were playing to a crowd. If you are having an argument in public, whether on an internet forum or in a pub, you should be aware that you’re playing to the gallery, not to convince whoever you are disagreeing with. Calling them an imaginative insult may be personally satisfying or even get a laugh, but it is hardly the high-ground of someone who is winning the argument.

If you are truly disagreeing with someone you couldn’t care less for, you need to ask yourself why you’re having the argument in the first place. As hard as it is to resist in a world of Twitter, Facebook and endless other online forums, you don’t need to stay up all night trying to best a stranger, just because someone is wrong on the internet.

That can be easier said than done, and I absolutely have been the person arguing with a stranger late at night on the internet. If we are arguing with someone online – which is reasonably likely in our 2020, given everything going on – we should probably bear in mind that we are not likely to convince our opponents of their error, at least on the first go, and especially not for more emotive topics.

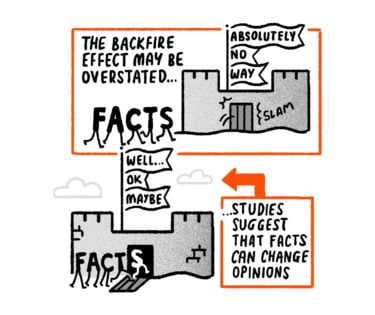

It has been said that challenging someone’s position with facts can have the opposite effect, reinforcing rather than challenging those beliefs.This so-called backfire effect is itself subject to some recent scrutiny, and studies suggest that facts can indeed change opinions. Your efforts are not a lost cause!

I’ve found myself in the middle of a chat during after-work drinks with workmates, and the subject of fortune-telling and mediums came up. People were interested to hear a colleague’s wild and unusual experiences with spiritualist churches and the like, and I doubt I’d have changed anyone’s minds there and then if I’d interjected. I’d just have come across as a boor. By contrast, an office colleague once mentioned they had a cold coming on, and wondered aloud whether they should get some Vitamin C; another workmate shouted up that there was no evidence it worked, and was just a myth – a far more appropriate time to inject some skepticism into the conversation.

You may be onto more fertile ground with a close family member who you see regularly. People will become more receptive over (a very long) time, and may come to believe that they agreed with you all along, or that the idea was their own. As said before, self-affirmation is important. I think I have helped to convince a family member of climate change – not through big set-to debates but by repeated mentions of the evidence and questions about their position, in the hope they’d come around. Why do I think I’ve (helped to) convince them? They no longer speak enthusiastically about the ‘climate change hoax’. Nobody ever announced I’d “won” – but their opinion quietly changed over time – and isn’t that what we really want?

Finally: if we’re going to be good skeptics, we need to be open to the possibility we’re wrong. For example, the Vitamin C conversation mentioned above? The current evidence is that although it won’t prevent colds, it may actually shorten the duration of a cold slightly, though there’s currently no strong evidence for a big effect. Next time I get a cold, I’ll probably just stick to taking paracetamol and feeling sorry for myself.