Despite all of our glorious diversity, there may be just two kinds of people in this world: those who believe that everything happens for a reason, and those who don’t and accept that chance plays a large part.

In the U.S., where a majority believe that God is in control of everything that happens in their lives from conception to death, it is rare to see acknowledgment of the role of chance in the world. After every disaster, one can count on press stories like that of an Alabama family who survived an EF-4 tornado by taking shelter in a prayer closet. “My God is Awesome!” proclaimed one chaplain upon seeing the still-standing structure, while neglecting to mention the twenty-three neighbors who perished.

It should not be too surprising then that two-thirds of American believers of all faiths see the novel coronavirus as a message from Above, rather than merely the accidental spillover into humans of a randomly mutating animal virus. We are treated almost daily to statements such as those of a Virginia pastor who justified holding services in defiance of crowd limits saying, “I firmly believe that God is larger than this dreaded virus. You can quote me on that.” He subsequently contracted the virus and died. Or stories like that of former Presidential hopeful Herman Cain, who attended a Trump rally without a mask and – two days after testing positive but before disclosing the fact – tweeted his support for shunning masks and ignoring distancing at another rally. After his diagnosis, Cain’s spokesperson stated, “With God’s help, we are confident he will make a quick and complete recovery.” Cain died four weeks later.

And so, we have a President who says he is “very impressed” by a doctor who believes demons cause illnesses.

The aversion to reason is enough to make we scientists despair. Where can we turn for hope?

I turn to comedy.

The late humourist Kurt Vonnegut, for example, frequently touched upon our accidental existence and struggle for meaning in his works. In his quasi-autobiographical novel Slapstick (1976), Vonnegut tells the story of the death of his sister Alice from cancer at age forty-one. He and his brother Bernard visited her on what would be the last day of her life.

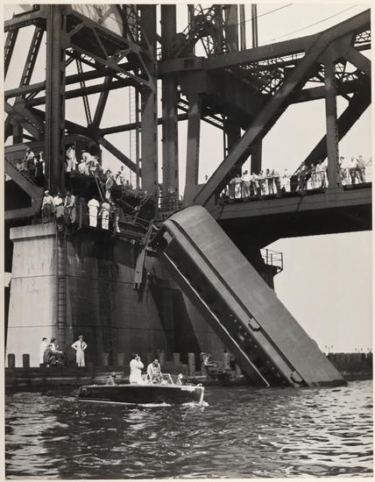

“(H)ers would have been an unremarkable death statistically, if it were not for one detail, which is this: Her healthy husband, James Carmalt Adams, the editor of a trade journal for purchasing agents, which he put together in a cubicle on Wall Street, had died two mornings before—on ‘The Brokers’ Special,’ the only train in American railroading history to hurl itself off an open drawbridge.

“Think of that.

“This really happened.”

The great satirist manufactured many fantastic scenarios in his tales, but the train wreck really did happen just as he said. On the morning of September 15, 1958, a New Jersey Central commuter train carrying about 100 passengers toward Jersey City somehow drove slowly through three signal lights and an automatic derailer and carried on 550 feet before plunging 50 feet off the open drawbridge. Two coaches of the five-coach train hit the water while a third dangled mid-air for more than two hours. Despite the heroic efforts of rescue crews, forty-eight people died, including Vonnegut’s brother-in-law.

Given his sister’s grave condition, and her concern for her four young children who were about to be in the sole care of her husband, Vonnegut and his brother elected not to tell her about the tragedy. She found out anyway when a fellow patient gave her a copy of the newspaper and she saw her husband among the list of the dead or missing. Vonnegut describes her reaction, and his own:

“Since Alice had never received any religious instruction, and since she had led a blameless life, she never thought of her awful luck as being anything but accidents in a very busy place.

“Good for her.”

Accidents in a very busy place, indeed.

As scientists have learned more about the history of the planet and the inner workings of life, it is irrefutable that we are all here, both collectively and individually, through a series of accidents. The course of life has been buffeted by a variety of cosmological and geological accidents – an asteroid impact, tectonic collisions, Ice Ages and more—without which our species would not exist. We each enter the world as a unique genetic accident, one fortunate combination of sperm and egg out of more than 70 trillion different babies our parents could make. And many of us will exit the world, like Alice, due to what we now understand to be an unfortunate combination of random mutations accumulated in our lifetime.

Vonnegut’s writings helped me to realize that, next to scientists, the one other group of people that seem least inclined to think everything happens for a reason, and rather that blind chance governs the world, are comedians. Many top UK performers such as Eddie Izzard, Ricky Gervais, Stephen Fry, and Billy Connolly, and a number of leading American comics including Bill Maher, Sarah Silverman, Seth MacFarlane, and Lewis Black reject traditional beliefs about the cause of events in the world, while making us laugh about the absurdity of those beliefs.

So many very funny people, in fact, that it made me wonder, why is this so? What do scientists and comedians have in common?

For insight, I reached out to Eric Idle, one of the all-time greats who with Monty Python and his other collaborators has created some of the funniest skits, films, and songs lampooning blind faith. He very kindly replied to my questions.

Carroll: Why do you think so many comedians conclude that there is no God?

Idle: It saves time.

Carroll: But why go public, why bring religion into your acts? Isn’t that risky for you? (Life of Brian was picketed or banned in various places)

Idle: Comedy is telling the truth. It’s the Emperor’s New Clothes. Everything is on the table. The Life of Brian is still playing after forty years…

I first saw Monty Python as a teenager. It never occurred to me then, and I confess that until recently I never really thought much about why I was laughing so hard – – they were trying to show me the truth? I thought they were just having a laugh. Is truth really the point of humor? Could I really be so clueless not to get that?

I also devoured Vonnegut’s novels when I was young. I searched interviews of the late writer to see what he had to say, and sure enough, he had a few pearls on the matter. I shared one with Mr. Idle:

Carroll: Vonnegut once said: “The telling of jokes is an art of its own, and it always rises from some emotional threat. The best jokes are dangerous because they are in some way truthful.” Your thoughts?

Idle: Truth is the point of comedy. It’s usually saying the right thing at the wrong time.

The scientist in me wanted more confirmation, so I looked for comments by my favorite stand-ups, and found several who echoed Vonnegut and Idle.

Ricky Gervais wrote about the importance of truth in an essay about the defining moment when he became an atheist. “[I] learned that day that the truth, however shocking or uncomfortable, in the end leads to liberation and dignity.”

I was excited by my newfound, albeit belated insight into comedians as truth-tellers. But my greatest delight from these comedy masters came when I discovered their strong embrace of science, and our kinship as fellow truth-tellers.

“Science seeks the truth. And it does not discriminate.” Gervais wrote in another essay. “For better or worse it finds things out. It doesn’t hold on to medieval practices because they are tradition. If it did, you wouldn’t get a shot of penicillin, you’d pop a leach down your trousers and pray.”

Vonnegut declared, “I love science. All humanists do,” and offered this vignette as evidence: “We once had a memorial service for Isaac Asimov [a biochemist and popular science and fiction writer], and at one point I said, ‘Isaac is up in Heaven now.’ That was the funniest thing I could have said to a bunch of Humanists. I rolled them in the aisles. It was several minutes before order could be restored.”

Vonnegut’s story is a tip that perhaps how we communicate science or its implications may be worth re-examining. Most scientists are convinced that if people just had the information we carry around in our heads, if they only knew what we know, then all would be better in the world. That is probably so, but perhaps it is not our message but our methods that fail us?

Vonnegut’s strategy was time-tested. “When Shakespeare figured the audience had had enough of the heavy stuff,” the novelist once told Playboy, “he’d let up a little, bring in a clown or a foolish innkeeper or something like that, before he’d become serious again. And trips to other planets, science fiction of an obviously kidding sort, is equivalent to bringing in the clowns every so often to lighten things up.”

What do we scientists bring after the heavy stuff? Usually more heavy stuff. I don’t recall the IPCC ever using a fart joke or a Martian to explain climate change.

I asked Mr. Idle, a huge science fan, about his approach:

Carroll: You have collaborated with Brian Cox and had a good laugh with Stephen Hawking [in The Entire Universe]. Humor, science fiction, cartoons, songs – maybe scientists have something to learn from comedy about ways to make a point?

Idle: Well the point about Science is that it can be tested. Comedy is tested on the audience. If they laugh it works.

And maybe, just maybe, comedy is working in ways we scientists have not succeeded or appreciated. I shared some encouraging data with Mr. Idle:

Carroll: Current 18-29 year-olds in the US are the least religious generation by far. Do you think that, collectively, comedians just might be having an influence on attitudes toward religion?

Idle: I certainly hope so. After all Religion is about the Ape evolving a set of moral standards. This would be significant in any Universe.

Can we hear an ‘Amen’?

Excerpted and adapted from A Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and You (Princeton University Press, October 2020).