“In these books the Devil stands stripped of all his brute disguises. Here are all your familiar spirits – your incubi and succubi; your witches that go by land, by air, and by sea…”

― Arthur Miller, The Crucible

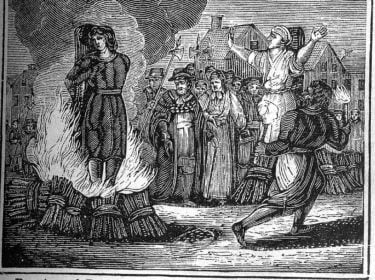

Perhaps one of the most well-known cases of mass hysteria and paranormal happening in recorded history are the Salem Witch Trials. Spanning over a year, from 1692-1693, over two-hundred men, women, and children were accused of witchcraft (defined here as using the powers of the Devil) in the town of Salem, Massachusetts. At the end of the events, forty-four people confessed to being witches, nineteen were hanged, five died during their imprisonment, one individual was pressed to death, and two dogs were shot.

The sheer amount of terror the town and close surrounding villages faced concerning witches and witchcraft compelled them to kill well over twenty people. But often-overlooked in the horrors of the Salem Witch Trials was the suffering experienced by those who claimed to be ‘afflicted’ by the witches. Accounts from the alleged victims included violent convulsions, muscle spasms, and the vomiting of blood, bundles of hair, sewing pins, needles, glass, faeces, cat fur, random bones, bird feathers, and metal scraps.

Further, fits of delusions and hallucinations plagued them, as well as night terrors. The afflicted would wake up during the night, usually screaming, to scratches, bites, and other unidentified marks supposedly made by the witches during the victims’ vulnerable slumber.

This evidence, if we discount complete fabrication, is intriguing and, even now people question how some of these findings may be physically and scientifically possible. Was Salem truly terrorised by people who had pledged themselves to the Devil? Was demonic possession or God’s wrath to blame for these events? Or is there a psychological explanation for seemingly paranormal attacks and symptoms?

Salem society

The Puritanical society of 17th century Salem was, quite simply, a difficult society to live in. It was extremely restrictive; singing, dancing, playing games, exploring, or going into the woods were not permitted. Attending church every Sunday – and whenever else other services were offered – was expected. If you missed church, it would inevitably come back to bite you, as seen explicitly in the witch accusations. Many held the viewpoint that the Devil was constantly attempting to corrupt individuals, and that everyday life was a battle between good and evil.

Beyond this, society was very patriarchal; women held little to no independence. Arguably, children had it worst: taught to be seen and not heard, they were expected to do their chores and work without complaint. Their chores were far more than simply making the bed or washing the dishes; children in Salem assisted in most areas of work – including chopping firewood, mending and sewing clothes, cooking, cleaning, and other hard labours. Children began to help their families around the age of four or five, and the toll of their work only increased as they grew.

There was very much a culture of suppression and stress placed on children in this way of life. Children were not allowed to partake in the things that made them children, and could not develop a sense of imagination or have a release from the pressures of society, as children were taught to not express emotion nor think independently.

It is therefore quite easy to understand why young girls were the demographic which were first affected by these mysterious symptoms in Salem. Doubly-oppressed as both children and women, these individuals truly faced the brunt of societal pressure. It is then quite possible that the Salem Witch Trials were a case of Mass Conversion Disorder due to a high stress and demanding social sphere, alongside the disorder Pica, and that these ultimately led to the famously historical witch hunt craze.

Mass Conversion Disorder explained

Mass Conversion Disorder (MCD), also known as Mass Psychogenic Illness or Mass Hysteria, is labeled as both a dissociative disorder and a somatoform disorder by two separate diagnostic scales, the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV. A dissociative disorder is defined as a “disorder that involves disruptions or breakdowns of memory, awareness, identity, or perception” while a somatoform disorder is a mental disorder that results in largely inexplicable physical manifestations (symptoms).

Specifically, MCD is a disorder that affects a cohesive group of persons, likely within the same social sphere and quite common in tightly-knit communities. There is perhaps no greater an example of a tight-knit community than the Puritans: almost cult-like in their religious devotion and quickness to band together to condemn sin and profess someone as doing the Devil’s work.

MCD is also commonly attributed to female communities with vast social pressure and constriction. For example, in 2012 a group of cheerleaders from Le Roy, New York, were diagnosed with MCD, and their symptoms may sound eerily familiar: muscle spasms leading to uncontrollable twitching and jerking, extreme vomiting, intense delusions and hallucinations. Also common were bouts of the sensation of being pricked by pins, as well as loss of sensation altogether.

Many explanations were given for their condition, from the HPV vaccine, to a chemical spill on the grounds of the school, to, even, demonic interference. Three hundred and nineteen years after the end of the Salem Witch Trials, the same physical symptoms manifested in a group of young girls under extreme social stress, and people still suggested the paranormal explanation of demonic possession. It is of little surprise, then, that the 1692 Puritans would believe it to be witchcraft and the Devil’s work.

The 1992 case is not the only recent case of MCD to be reported – a similar case occurred in 2002 in a North Carolina high school, once again among cheerleaders. It happened again in 2007 at an all-girls Catholic boarding school in Mexico City. Three well-known, well-documented cases in the present of circumstances eerily similar to those presented in Salem in 1692. The scientific precedent of MCD affecting young females under extreme social pressure and in close-knit social spheres could clearly be a plausible explanation for the horrific symptoms of those afflicted persons in old Salem.

Those who question MCD as an explanation for the Salem experiences often point to what seems to be a flaw with the theory: the more intense symptoms. Throwing up needles, pins, and all sorts of other horrifying objects isn’t normal – at least not for most people. However, those affected by Pica would find the experiences much more familiar.

Classified as a compulsive eating disorder, Pica is characterised by eating substances with no nutritional value. Manifesting mostly in children and youth, The Handbook of Clinical Child Psychology currently estimates the prevalence of Pica to be between 4% to 26% of the world population. Most interestingly, Pica is found to accompany mental disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive compulsive disorders, depression, and intense anxiety disorders.

MCD, while not being specifically labeled nor categorised as one of these disorders, does, however, have the dissociative aspect of schizophrenia through delusions and hallucinations, and the obsessive compulsive aspect of scratching, hair pulling, and biting due to psychosomatic itching, loss of sensation, and nerve spasms. Therefore, it is not improbable to assume that Pica could arise in these girls due to their mental states and somatic reactions.

It is especially not improbable because, among the girls of Le Roy, half were found to have swallowed “strange objects”, and many others to have furiously scratched and bitten the skin on their back, thighs, and arms until they bled, often during fitful sleep or fugue-like states. What is most frightening about these events is that, more often than not, the girls did not remember eating the unusual objects, and only learned of it having received ultrasound, x-ray or CT scans. Neither did they notice scratching or biting themselves regularly, due to their bouts of pain desensitization and/or fugues. Given that we did not understand dissociative fugues or psychosis until well into the 1900s (and even now, not everything is known about these kinds of states), it is easy to understand how the people of Salem could assume a paranormal cause for girls vomiting unusual objects and finding unexplained scratches and bite marks.

Ultimately, there is no way to know for sure if any of the theories posited concerning the Salem Witch Trials are true. Whether it was paranormal, psychological, fabrication or something else, the Salem victims are perhaps the most discussed and researched set of individuals to have claimed relation to witchcraft. And despite modern advances in medicine, science, and technology, when situations like the three current-day incidents of 2002, 2007, and 2012 occurred, there were still some people who offered demonic interference and witchcraft as viable explanations.

Ascribing paranormal origins to events that humans cannot immediately comprehend is such a strong and persistent instinct in society that even the most intense and bloody witch hunt could not eradicate it. From 1692 to 2012, these phenomenons showcase the persisting strength of humankind in their beliefs of the paranormal, and the paranormal’s everlasting ability to enchant and terrify the masses. Perhaps that is true witchcraft.

References

- Ali, S., Jabeen, S., Pate, R. J., Shahid, M., Chinala, S., Nathani, M., & Shah, R. (2015). Conversion Disorder – Mind versus Body: A Review. Innovations in clinical neuroscience, 12(5-6), 27-33.

- Aybek S, Nicholson TR, O’Daly O, Zelaya F, Kanaan RA, David AS (2015) Emotion-Motion Interactions in Conversion Disorder: An fMRI Study. PLoS ONE 10(4): e0123273.

- Baker, Emerson A. A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience., 1 December 2015, Pages 1880–1881.

- Bartholomew R, Rickard B. “Mass Hysteria in Schools: A Worldwide History Since 1566”, (2015) History of Education Review, Vol. 44 Issue: 1, pp.131-133.

- Beat Eating Disorders. (2017, September). Pica.

- Blakemore, Erin, Women Weren’t the Only Victims of the Salem Witch Trials. History Channel. History.com.

- DeCosta-Klipa, N. (2017, October 31). The theory that may explain what was tormenting the afflicted in Salem’s witch trials.

- Dominus, S. (2012, March 07). What Happened to the Girls in Le Roy.

- Feinstein A., Conversion disorder: advances in our understanding. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne, (2011) 183(8), 915-20.

- Hatchman, Laura, (2013) “From Demonic Possession to Conversion Disorder: A Historical Comparison” . Honors Scholar Theses. 302.

- Hutchinson, T. & Poole, W. F. (1870) The Witchcraft Delusion of Boston, Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, Priv. print [Web].

- Moran, Gerald & Vinovskis, Maris. (1985). The Great Care of Godly Parents: Early Childhood in Puritan New England. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 50. 24. 10.2307/3333861.

- National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA), (2018, February 22), Pica.

- Nickell, Joe. “Neurological Illness or Hysteria? A Mysterious Twitching Outbreak.” Skeptical Inquirer 36, no.4 (July/August 2012): 30-33.

- Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, February 1974); John Demos, The Enemy Within (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2008), 190.

- Radiological Society of North America, Rsna, & American College of Radiology. (2018, July 16). Foreign Body Retrieval.

- Rosenthal, Bernard, ed. Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Simeon, D., & Abugel, J. (2006). Feeling unreal: Depersonalization disorder and the loss of the self. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- WebMD, (2005), Pica (Eating Disorder): Treatments, Causes, Symptoms.

- Zavala, Nashyiela Loa. “The Expulsion of Evil and its Corrupt Return: An Unconscious Fantasy Associated with a Case of Mass Hysteria in Adolescents.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 91, no. 1 (2010): 1157-1178.