There’s been much critique of social media giants and the influence their platforms have on discourse, democracy, and public health – and with good reason. While some of the claims about Facebook’s ability to microtarget users in order to wholly sway election may turn out to be a little overstated, it is hard to deny that tech platforms’ drive for engagement has inadvertently amplified conspiracy theory, health misinformation and maliciously-designed fake news.

In response to the criticism, companies now direct users and journalists to the efforts they are making to limit the spread of misinformation and disinformation: earlier this month Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram banned “any groups, pages or Instagram accounts that “represent” QAnon”; last week, Facebook overturned a long-standing policy to announce that holocaust denial will no longer be welcome on their platform, with Twitter swiftly following suit; and most recently Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook will no longer display advertising that discourages vaccination.

These changes are doubtlessly welcome, but it’s hard not to look at these policy shifts and to wonder: what took them so long? How long was Facebook accepting payment to display adverts that spread false information about the safety and efficacy of vaccines? How recently did they realise the adverts they were paid to show could be persuading people that vaccines were unsafe? These feel like pretty important questions.

While these new policies will go some way towards addressing the spread of misinformation, few who have followed these issues will believe the measures to be sufficient. Take, for instance, the ‘ban’ on anti-vax misinformation: it applies only to paid advertising, but not to any other form of anti-vax content on Facebook. Adverts which explicitly discourage vaccination would be non-compliant with the Committee of Advertising Practice Code, the set of rules which govern advertising claims in the UK. If Facebook was serving anti-vax ads to UK users, they would already have been in breach of these regulations.

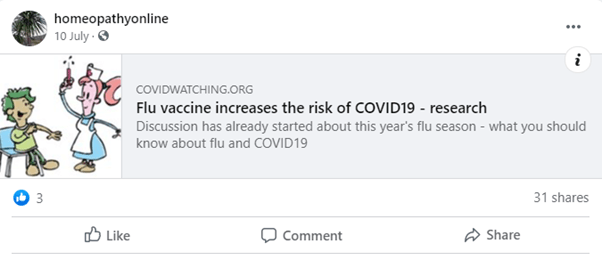

More importantly, in practical terms, it’s hard to see that this policy change will have any appreciable impact at all, because the overwhelming majority of anti-vax content spread on Facebook is done via groups, shared posts and pages – not through paid advertising. Facebook’s updated vaccine policy wouldn’t stop, for example, this post from being shared:

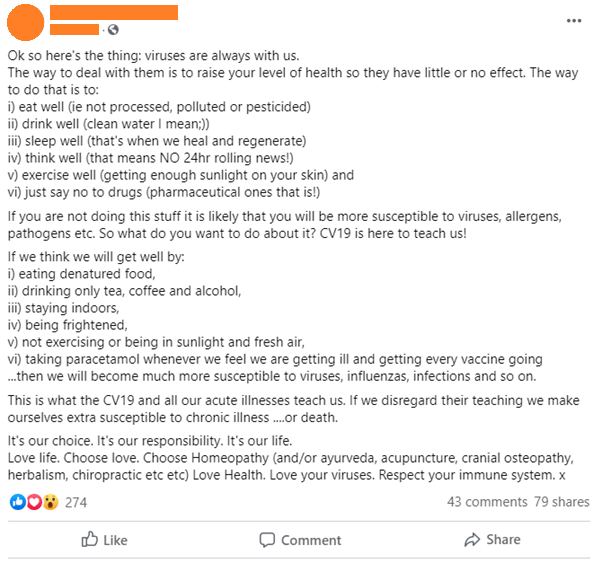

Nor would it stop this, from a member of the Society of Homeopaths:

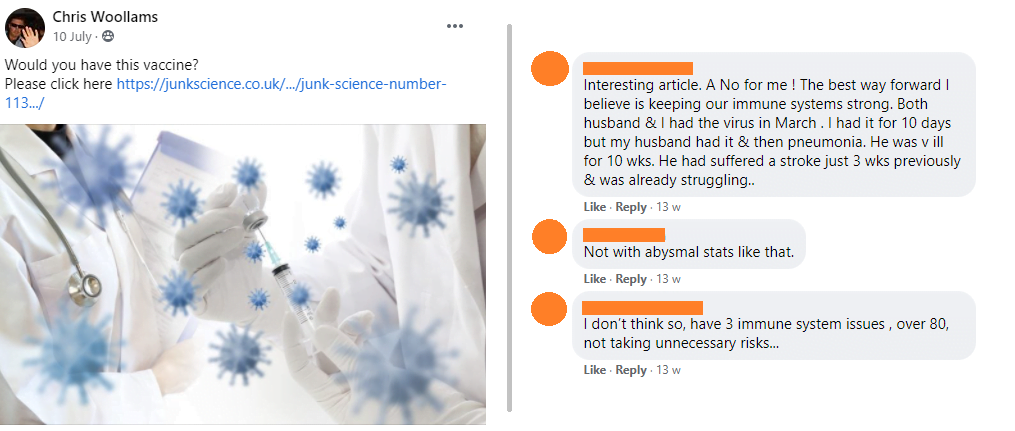

Or this, sharing an article from a website that has repeatedly published anti-vaccine misinformation:

In the comments, multiple users explain that they have health complications that leave their immune system comprised and put them in an at-risk population, yet they believe the risks of vaccination outweigh the very real risks posed to them by COVID-19. This is the coalface of the damage anti-vax misinformation can do.

Because none of these posts – or the thousands like them on personal feeds, in public and private groups, and in comments on pages – are paid advertising, none of them would be affected by Facebook’s new ban. Facebook has suggested that these kind of misleading claims would be picked up by other policies they have introduced to curtail the spread of vaccine misinformation, but these were just the first examples I found when I went to look, and no such counter-measures had been deployed.

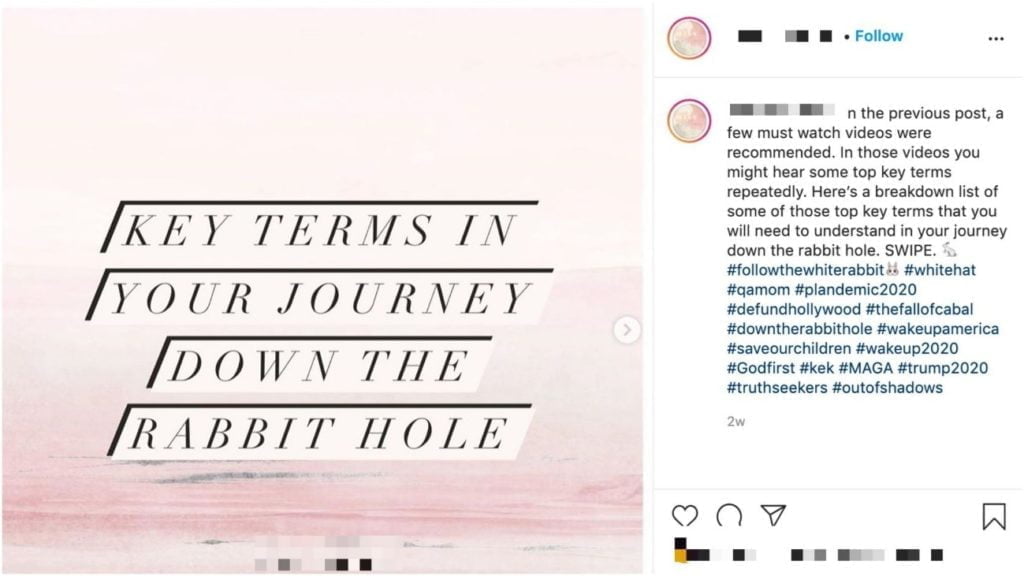

Facebook’s ban on QAnon content, too, is less impressive upon inspection. While the platform will remove accounts that “represent” QAnon, this will only apply to “groups, pages or Instagram accounts whose names or descriptions suggest that they are dedicated to the QAnon movement”. Crucially, this would not limit the spread of posts containing QAnon conspiracies shared by people from their personal accounts, or from groups and pages that are dedicated to other pseudoscientific topics – including other conspiracy theories, alternative medicine beliefs, fake cancer ‘cures’ and even the anti-vaccination movement.

This is a genuine problem, especially given the rise of “Pastel QAnon” – a term QAnon researcher Marc-André Argentino coined to refer to QAnon believers who are “lifestyle influencers, mommy pages, fitness pages, diet pages, and [have] alternative healing” accounts. Pastel QAnon launders QAnon messages and narratives into the timelines of people who signed up to see content in or adjacent to the health and wellbeing spaces, but without explicitly labelling those messages as part of the QAnon movement. Their posts normalise terms like “the storm” and “the great awakening” – terms I’ve even seen appearing on the Facebook feeds of my own family, who I don’t imagine for a moment understand these terms are signifiers of a conspiracy theory that believes a shadowy cabal of satanic paedophiles are soon to be brought to justice by Donald Trump.

Pastel QAnon, along with movements like “Save Our Children”, have allowed the conspiracy theory to jump streams and enter wider discourse, divorced of the explicit signs of the origin of these ideas.

The adoption by QAnon believers of “Save Our Children” as a slogan and rallying cry seems tailor-made (possibly deliberately so) to appeal to the communities who make up Pastel QAnon, and to offer the movement plausible deniability. After all, who could argue with the goal of saving children… as long as you aren’t forced to explain that the thing you’re saving the children from is a Satanic paedophile cult of senior politicians and international celebrities based on a blood libel that is nakedly anti-Semitic.

This cover is so successful that even mainstream publications like the Mirror and the Mail Online last month failed to spot they were being used as a vehicle for “Save Our Children” activists to spread paranoia about alleged paedophilia.

Given the rise of Pastel QAnon and the penetration of the conspiracy theory into the wellness movement, the flaws in Facebook’s efforts to tackle either anti-vax or QAnon posts unfortunately have a compounding effect: the accounts that promote misleading and scaremongering information regarding vaccines are the same ones now at risk of promoting entry-level QAnon content. Failure to tackle one of these issues is a failure to tackle the other.

This is a problem for which Facebook must shoulder some degree of responsibility: their role in the growth of QAnon goes beyond merely failing to arrest its spread. As the Guardian found out in an investigation in June, Facebook’s recommendation algorithm has actively been promoting QAnon groups to users who may not otherwise have been exposed to them:

“The Guardian did not initially go looking for QAnon content on Facebook. Instead, Facebook’s algorithms recommended a QAnon group to a Guardian reporter’s account after it had joined pro-Trump, anti-vaccine and anti-lockdown Facebook groups. The list of more than 100 QAnon groups and accounts was then generated by following Facebook’s recommendation algorithms and using simple keyword searches.”

The promotion of groups is significant, given that in early 2018 Facebook announced it had changed its algorithms away from promoting “relevant content” and toward “meaningful social interactions” – the upshot of which was that Pages would be de-emphasised, whereas content from Groups would be promoted:

The first changes you’ll see will be in News Feed, where you can expect to see more from your friends, family and groups. As we roll this out, you’ll see less public content like posts from businesses, brands, and media.

With content from groups fed more actively into people’s feeds, and groups with high engagement (likes, posts and comments) emphasised, it is little surprise that Facebook’s algorithm flagged QAnon groups as worthy of recommendation; I can think of few better sources of engagement than confused conspiracy theorists franticly competing to read meaning into the cryptic, opaque and nonsensical pronouncements of a supposed online whistleblower.

The QAnon genie is well and truly out of the bottle, proliferating far beyond the message boards it originated on, and far beyond the accounts and groups who spread it explicitly. Whether they like it or not, Facebook has been more culpable than any other platform in provoking and promoting the spread of this belief, and the steps they are proposing to fix it are wholly inadequate. This is, in part, their mess, and they need to be serious about cleaning it up.