I had only just recently stepped into the Big Shoes on The Skeptic’s editorial team when I gave a talk as part of a regular Sunday morning series at the home of free-thinking in London, Conway Hall. At packing-up time, I was approached by a small, aged attendee who smiled broadly as he introduced himself: “Hello. I’m Donald!”

Of course, I knew Donald Rooum’s work. He had generously contributed to the magazine since its earliest days, having written to founder Wendy Grossman after just the first issue to offer his services. Donald created the cartoon strip ‘Sprite’ for the magazine.

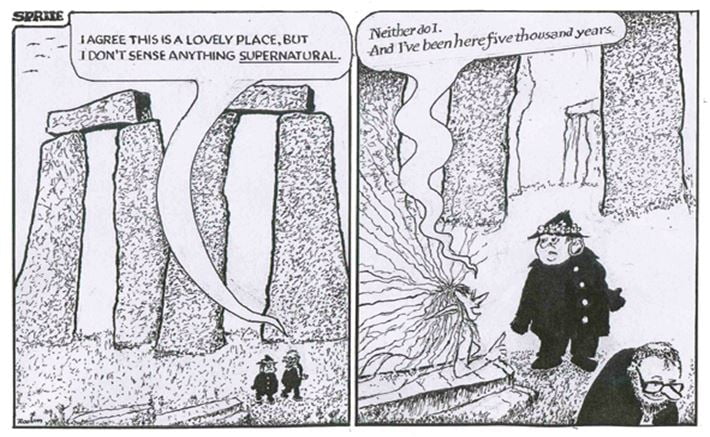

“The first character is named Donald and is based on me” he explained in an interview with The Comics Journal in 2002, “and the other character is Titania. She is a lady sprite who has a habit of disappearing into a swirl of smoke.” The love-struck Titania is always trying to reach through Donald’s scepticism, but it is so resolute that he simply cannot see her. “Some of the time I merely take a swipe at something in the world of the paranormal, but the best Sprite cartoons are the ones where I revert to the main plot.”

That meeting in London was the first of many – we moved in the same circles and bumped into each other often. The main thing that struck me was that, at an age when most people get a pass for snoozing, Donald was always sharp, alert… and smiling.

He had trained in commercial design at the Regional College of Art, Bradford for four years and became a professional typographer, later lecturing in typographic design at the London College of Printing until his retirement aged 55. His parallel career as a cartoonist saw his work appear in publications like The Daily Mirror, Private Eye and The Spectator and even the British women’s publication She. He greatly admired and was influenced by the British cartoonists who illustrated children’s comics in the early twentieth century – people like Reg Parlett, Roy Nixon, Ken Reid and The Bash Street Kids’ Leo Baxendale. Later, he expressed an admiration for underground comix artists Gilbert Shelton and Hunt Emerson.

But I suspect that Rooum will be most remembered for exposing corrupt British police officers in the notorious ‘Challenor’ case of 1962. Rooum was one of a group protesting against a visit to London by far-right and “inherently undemocratic” Queen Frederika of Greece when he was arrested. Officer Harold Challenor said “You’re fucking nicked my beauty. Boo the Queen, would you?” subsequently adding a rock to Rooum’s belongings: “Carrying an offensive weapon – you can get two years for that”. Fortunately Rooum had his solicitor take his jacket to a forensic scientist who confirmed that there was no trace of rock dust, or wear and tear in Rooum’s pockets, proving that the object could never have been there.

Rooum’s evidence led to an acquittal at his trial. A subsequent trial against Challenor and three other officers for perversion of the course of justice followed. Challenor avoided culpability, having been certified as suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, but his three colleagues were sentenced to three years each. A Parliamentary enquiry, in what became generally regarded as a whitewash, eventually exonerated Challenor and placed the blame for the incident on his mental condition as opposed to any institutional deficiencies. However, the blatant corruption and political biases within the Met., not to mention Parliament and the legal system, were exposed. Unusually for a person suffering from paranoid schizophrenia – a chronic condition for which drugs in the ‘60s weren’t up to much – Challenor was subsequently employable enough to find work with the firm of solicitors who had defended him.

Donald’s retirement from teaching at the London College of Printing freed him up to spend more time on art and his lifelong political interest in anarchism. He was a devoted volunteer at Freedom Press, an imprint which has published seven collections of his fortnightly cartoon ‘Wildcat Anarchist comics’. The strip takes stereotypes and gently prods at hubris within political movements. I recommend them. He was a humanist and a keen supporter of Humanists UK. He noted that many of his anarchist colleagues could be anti-science, but he himself was pro-science, even having gained a first class degree in Life Sciences in adulthood.

Donald’s partner was Irene Brown, with whom he had three daughters and a son. To judge by the attendance at his memorial gathering at Conway Hall in January of this year, he also had a large group of loving friends who regarded him very highly.

Founder of The Skeptic, Wendy Grossman said to me: “It’s a great loss. He was a defining part of the look and feel of The Skeptic. Humour is a crucial part of both the magazine and skepticism in general.” Former editor Professor Chris French said “The thing I loved most about Donald’s cartoons was that his gentle humour was as likely to be making fun of sceptics as it was of believers. He recognised the irrationality in all of us.”

Donald Rooum had a life that was very fully lived. He contributed greatly to free-thought causes all his life. And he was sparkling and alive in a way that many people don’t manage to maintain over a whole lifetime. R.I.P Donald. We will miss you.