There’s an old aphorism that runs, “There are no atheists in foxholes.”

I’ve never been quite sure whether this means that when you’re hiding out in a war zone with death all around you, no matter what you actually (don’t) believe you instinctively pray for help because there’s nothing else to do… or that atheists in such situations suddenly discover the inner devout believer they’ve had the luxury to deny existed until now. I’ve always hoped the former. Who wants to find out in extremis that they’re a lifelong hypocrite?

One of the most interesting things about the ongoing pandemic is the extent to which so many people are suddenly eagerly embracing science for answers and advice. There are exceptions, such as Congressmember Devin Nunes (R-CA), who as late as March 14 posted a video clip on Twitter telling healthy people they should go out and support their local empty restaurants and bars. And, it emerged in early April, a bunch of people in Britain bought into the hoax claim that the incoming fifth generation of mobile networks (5G) are a vector for spreading the virus and accordingly have vandalised or set fire to a number of completely unrelated mobile masts.

I’ve thought before that whatever they think they think or say they think, people’s behaviour in a crisis often betrays an inner cognitive dissonance. In 1987, soon after I founded The Skeptic, the weekly spiritualist newspaper Psychic News reported that burglars had broken into its London office. And – with no apparent awareness of the irony – they reported that they had called the police to investigate. The police. Not their best psychics.

I remember this recently, when the Catholic Herald announced that on February 28 the Lourdes shrine closed its healing pools as a precaution against spreading the coronavirus. Read the note on its website: “Our first concern will always be the safety and health of the pilgrims and the shrine’s working community. As a precaution, the pools have been closed until further notice.” Oh, really?

It turned out the shrine was still permitting pilgrims to visit; it didn’t close down celebrating public mass for another couple of weeks. Even so, it clearly suggests that the people running the operation know perfectly well that they’re selling false hope, not miracle cures. The reality is perfectly captured in a famous quote usually attributed to Émile Zola: “The road to Lourdes is littered with crutches, but not one wooden leg.”

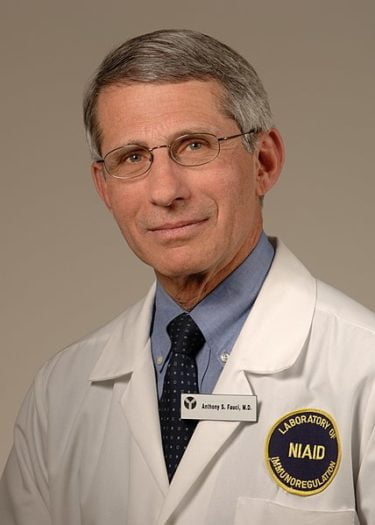

In this atmosphere, when the general public is abruptly listening to scientists, in the US two plain-speaking heroes are emerging. The first is the epidemiologist Antony Fauci, a New Yorker of Italian descent whose storied history includes work on every health crisis since the emergence of HIV/AIDS. The second is the even more blunt, combative New York state governor, Andrew Cuomo, son of Mario, who governed the same state in the 1980s, when I lived there. “No one likes him,” says an New York state-based online acquaintance – but in this crisis he’s become an unlikely star – the grim figures in the country’s most-ravaged city presented with the honesty and empathy missing from the president. For many of us, the facts are less frightening than fantasies that will go bust. This is a crisis a con artist cannot lie, deny, bargain, bluster, or bully his way through. Reality has a way of blowing up bullshit.

That said, unassailable facts may up-end people’s beliefs, but they don’t help heal divisions, and these days they don’t change people’s minds. It seems to me perfectly possible that the top-layer belief can mutate from “the virus is a hoax” to “my friend’s in a coma” without dislodging the longer-term, more deeply-held belief by his base that “Donald Trump is doing a good job, and when he’s failed it’s because evil Other People undermined him”. Even against the worst COVID-19 numbers, that belief will spring eternal, no matter how much detail the press can find to show otherwise.

New Humanist recently ran a fascinating essay by Eleanor Gordon-Smith, who argues that the key to persuading people is connecting to their emotions. Emotional engagement has long been an issue for skeptics, who are often accused of being cold, negative, and closed-minded. In 1976, when CSICOP was founded, people disagreed about interpretations but could mutually accept a set of facts; today that common base is gone, replaced by clashing sets of incompatible claims. As The Skeptic enters this new phase, being taken over by its fifth editor (sixth, if you count my 1987-1989 and 1998-2000 stints separately), finding new ways to understand and engage with people’s emotional connections to beliefs that are unsupported by evidence will be increasingly important. As our new leader put it in a recent email, while many skeptics like to say that “Facts don’t care about your feelings”, it is also true that “Feelings don’t care about your facts”.

For now, however, let’s close with the US Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, who wrapped up the passage of one of the coronavirus-related legislative packages: “To those who choose prayer over science, I say that science is the answer to our prayers.” Amen.

Wendy M. Grossman (www.pelicancrossing.net) is founder and (twice) former editor of The Skeptic, and a freelance writer.