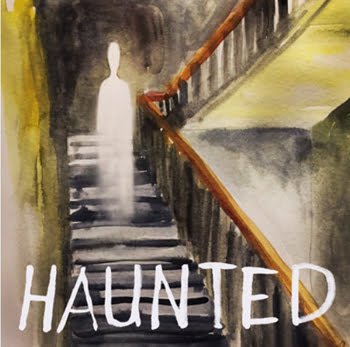

This is the deceptively simple question I ask at the beginning of every episode of the Haunted podcast. The show features ghost stories that have come to me through social media. I interview the person who had the experience and, with the help of sceptically-minded experts, offer possible reasons for what they saw.

What pleases me when I do that thing all podcasters do – feverishly scour the reviews on iTunes – is that the show seems to be enjoyed in equal measure by sceptics and believers. It’s not an easy trick to pull off. We live in an age more attuned than ever to the power of words. In the fields of race-relations, gender politics and trans-activism, we see examples of the emotive force of a single word, but, until I made Haunted, I hadn’t fully considered the divisive, incendiary impact of the word ‘ghost’.

In our increasingly unshockable world where awful things fill our social-media feeds until we become jaded and immune, punch drunk from horror, the statement “I have seen a ghost” still has the power to elicit real shock. Those words can silence a room and forever change the way we see someone. Imagine how you, as a sceptic, would react if your friend or partner became convinced they had seen the dead come back to life.

Terminology & Ontology

‘Ghost’ is a dirty word.

So, right now, I’m going to do my best to reclaim it, because I believe we need to reboot the terms of the debate. We’ve been locked in a binary shouting match with sceptics on one side, armed with a convincing battery of scientific explanations, and, on the other side, paranormalists fuelled by the adrenaline rush of late nights in haunted locations and the conviction they have seen something science cannot explain.

And into the cracks caused by this seismic rift, fall the sort of people I found myself talking to on Haunted. Ordinary folk who assumed ghosts don’t exist but then saw something that gives them doubt. Aware of the social stigma of telling people about their experience, they kept it to themselves.

Human beings need ghosts … (they are) the supernatural equivalent of Japanese knotweed.

It’s people like this that make me realise the sceptic community is highly skilled at explaining how strange phenomena occur, but sometimes less interested in why. In the battle to prove that ghosts don’t exist, it is easy to overlook the thing that is staring us in the face: they clearly do. By which, I mean that people do experience things which they think are ghosts and, as soon as they take the step of believing, the ghost becomes real to them. It starts to have a tangible effect on their life. It, in short, exists.

It’s often remarked upon that paranormal experiences have followed certain patterns throughout history. Believers cite this as evidence that ghosts are real whilst sceptics see it as the contagion of belief; each ‘ghost’ the echo of its antecedents. What I think it proves more than anything though is how very much human beings need ghosts; how deeply rooted and hard to shift they are in our psyche. The supernatural equivalent of Japanese knotweed.

Despite the concerted efforts of sceptics, we as a species, are unable to consign ghosts to the scrapheap of redundant belief. There are many people who don’t believe in God but do believe in ghosts, and there are many more who do not believe in ghosts but wouldn’t dare to spend the night in a ‘haunted’ house, because, deep down, a tiny bit of them does believe, just enough to get scared.

A Sign of the Times?

(are ghosts) a collective longing for magic, hope and comfort in a world that feels bleak and cruel?

There is a clearly a renaissance in supernatural interest at the moment. There’s a resurgence in exorcisms in both the Christian and Islamic faiths; horror films rule at the cinema; the ghost story is an acceptable literary form again, and podcasts like mine, Lore, The Black Tapes and Haunted Places have brought creepy tales to a digital audience keen to tingle their spines on their daily commute.

From a sceptic point of view, it would be easy to see this ‘ghost-boom’ as a sign of the times: irrationality and naked belief triumphing over science and rationalism; in-keeping with the anti-expert narrative that arguably brought us Trump and Brexit. However, it’s possible to read it as a sign of the times in a different way; as not an extension or symptom of the irrational chaos of a world run by a dangerous Reality TV star with his finger on the nuclear button, but a response to it; a collective longing for magic, hope and comfort in a world that feels bleak and cruel.

Because, at the heart of the thorny, divisive issue of ghost belief lies the paradox that something so redolent with death is also deeply comforting. Ghost stories, by exposing us to the exhilaration of terror in a contained way, reinforce the security of our own existence. And ghost sightings can bring comfort too. By far the most moving episode we made of Haunted featured bereaved people who felt they had been contacted by the spirits of their loved ones. These were people unexploited by ambulance-chasing psychics, who simply took joy from the idea that they could have a connection with the person they loved. This might take the form of something as simple as a picture falling off a shelf at the moment they thought of the person, but, through the filter of grief, it became proof of contact. From either a sceptic or a believer’s perspective, these ghosts were therapeutic vehicles for dealing with grief. Real or imagined, they brought tangible comfort.

If we expand that to society at large, we can make a case that ghosts are our defence against humankind’s greatest enemy: death. They’re our way of processing the horrific thought that one day we, and all we love, will no longer exist. As such, they are not irritating superstition, but cultural and social necessity.

The sceptic and paranormal investigator Hayley Stevens, who acted as one of our experts on Season 1 of Haunted, wrote a very moving blog about how the death of her mother changed her attitude to ghosts. In her bereaved state, the inexplicable flickering of a lamp in her house implied a presence and sparked an internal conflict between her sceptic head and her broken heart, which craved the person she missed. In bereavement, the debate about the existence of ghosts is no longer abstract.

Perhaps sceptics need to be careful what they wish for in seeking to stamp out irrational belief and dissolve ghostly shadows under the powerful floodlights of reason. There is much good work to be done by offering people scientific, rational explanations for their ghostly experiences. These explanations can serve the brilliant purpose of combatting fear – either that a house is haunted or that the person themselves is mentally ill. But, sometimes we do need ghosts. They are a necessary buffer between life and death, and a world without them, an entirely sceptic universe, with every corner, nook and cranny illuminated and nowhere for the dead to hide, or for us to hide from death – that is a frightening idea.

I’ll end with another question then: not “do ghosts exist”, but can we exist without them?

Danny Robins is a writer, broadcaster and journalist. He writes scripts for TV and Radio and presents the Haunted podcast.