Tessa Kendall looks at primatologist Frans de Waal’s work to muse upon the origin of our better natures

Is human nature a beast that needs to be tamed? Should we “throw out Darwinism in our social and political lives”? Or are we naturally altruistic, empathetic and moral?

Is human nature a beast that needs to be tamed? Should we “throw out Darwinism in our social and political lives”? Or are we naturally altruistic, empathetic and moral?

In Frans de Waal’s new book, The Bonobo and the Atheist, he takes on the thinkers who believe that morality has to be imposed on our brutish natures and catalogues the growing evidence that disproves them.

There is a long history of thought that the natural world is a merciless struggle for survival and that humans decided to live together ‘by covenant only, which is artificial’ (Hobbes), that natural selection is “a Hobbesian war of each against all” and ethics are humanity’s cultural victory over the evolutionary process (Huxley), that civilization is achieved through the renunciation of instinct and the action of the superego – which men are more capable of than women (Freud), that small children have to be trained to be sociable through fear of punishment and desire for praise (Freud, Skinner, Piaget), that moral behaviour is achieved through reason alone (Kant). A step away from this idea but on the same continuum is the idea that we are potentially but not naturally moral (Ridley).

These ideas have their origins in the Judaeo-Christian teaching that morals have to be imposed from above, that in our ‘natural state’ we are unfit for society because of original sin.

What all these thinkers have in common is a kind of dualism between our ‘better angels’ and the beast within, our Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. More recently, a lack of understanding of the difference between predation (of other species) and aggression (towards our own species) led to the popular and persistent image of humans as ‘killer apes’.

The idea persists even now, albeit stripped of its religious origins. Richard Dawkins, for example, has said that “we, alone on earth, can rebel against the tyranny of the selfish replicators” (The Selfish Gene) and that “in our political and social life we are entitled to throw out Darwinism, to say we don’t want to live in a Darwinian world”.

Some disagree. Darwin is one of them. He wrote that “any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts (…) would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience, as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well developed, or nearly as well developed, as in man” (Descent of Man). Stephen Jay Gould wrote in 1980 “Why should our nastiness be the baggage of an apish past and our kindness uniquely human?” Philosopher David Hume believed that moral sentiments come from “a tender sympathy with others”.

De Waal agrees with them. He does not believe in any inner dualism, in the need to choose to be moral or to accept moral instruction from above (gods, philosophers or authority figures) because altruism, empathy and morality are innate in us. What’s more, they also exist in other social animals. They are part of an evolved package of behaviours that make it possible for us to be social animals. He calls the idea that civilization and morality are imposed on a violent, immoral, selfish nature ‘Veneer Theory’.

He is not idealising humans or other animals. Conflict is inevitable. It is how and why we resolve or avoid it that matters. He also underlines the difference between humans and some other social animals: “What is so interesting about human prosociality is precisely that it is not of the ‘eusocial’ kind, which promotes sacrifices for the greater genetic good. We, humans, maintain all sorts of selfish interests and individual conflicts that need to be resolved to achieve a cooperative society. This is why we have morality and ants and bees don’t. They don’t need it.”

For many years, De Waal’s claim that other animals display altruism and empathy was ignored or rejected. What his latest book achieves is to put onto a firm evidential basis the fact that the roots of our social behaviour can be seen in other animals. The critical issue is no longer whether animals have empathy, but how it works.

For example, research has shown that moral decisions involve areas of the brain in humans and other animals that deal with emotions and – significantly – the evaluation of others’ emotions. Human morality is “firmly anchored in the social emotions, with empathy at its core” (De Waal, Our Inner Ape). The desire to treat others well comes from altruism which, in turn, comes from empathy.

For example, research has shown that moral decisions involve areas of the brain in humans and other animals that deal with emotions and – significantly – the evaluation of others’ emotions. Human morality is “firmly anchored in the social emotions, with empathy at its core” (De Waal, Our Inner Ape). The desire to treat others well comes from altruism which, in turn, comes from empathy.

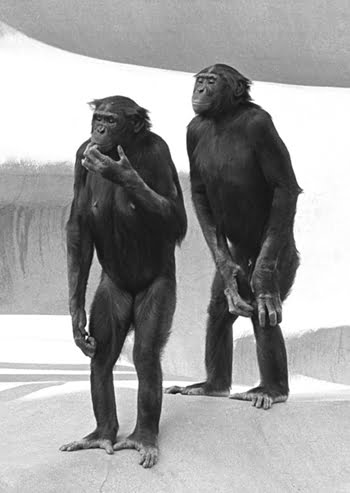

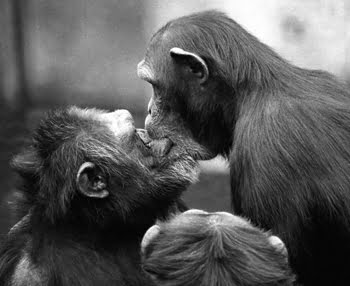

There is strong evidence in other animals of reconciliation and consolation after conflict – kissing, embracing and grooming for example, to restore social bonds. They are aware of unfairness – what economists call inequity aversion – which makes good sense in the avoidance of conflict. This has been seen in animals as diverse as capuchins, elephants, canids and corvids. They co-operate and form social ties, both of which improve survival chances – female baboons with the best social ties have the most surviving offspring, for example. Co-operation is strongest in meat-eating animals as hunting requires co-ordination and meat-sharing to provide a reward. Vegetarian animals are much less co-operative because they don’t need to be.

Social animals show gratitude and revenge – remembering the behaviour of others and paying them back. They target their helping, which requires being able to see a situation from another’s point of view. They are able to delay gratification, which shows self-control – a characteristic thought to be only human. Some are aware of the emotional states of others. When VEN cells in humans are damaged there is a loss of self-awareness and empathy; these cells exist in apes, cetaceans and elephants – but not monkeys.

A recent study “highlights the fact that, similar to humans, sensitivity to the emotional states of others actually emerges very young in bonobos and may not require so much complex cognitive processing as has previously been assumed”. Small children comfort other distressed children, even before they have developed the language skills to be instructed to do it.

Part of the problem of resistance against altruism and empathy in other animals is human exceptionalism, the idea that humans are in some way special, set apart. This too has its roots in religion, with humans as God’s special creation, the only creature possessed of a soul. It has persisted for a surprisingly long time in a secular form both in science and the humanities but is slowly being eroded. De Waal has written: “Humanity never runs out of claims of what sets it apart, but it is a rare uniqueness claim that holds up for over a decade. This is why we don’t hear anymore that only humans make tools, imitate, think ahead, have culture, are self-aware, or adopt another’s point of view”.

He also notes that religions developed in countries where there were no other primates have the strongest tendency to set humans outside nature – they have no animal gods or animal-headed human gods.

He acknowledges that humans have more complex and developed social skills; we alone analyse, discuss and codify our behaviour. He says “I am reluctant to call a chimpanzee a ‘moral being’. This is because sentiments do not suffice. We strive for a logically coherent system”.

Human morality and laws show “a move towards universal standards combined with an elaborate system of justification, monitoring and punishment” – for example the Geneva Convention and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In animals there is what is called motivational autonomy – they don’t think about why they do something – for example, they don’t make the link between sex and reproduction or between sharing and surviving.

The only possible exception I can think of (so far) is the arts. No animals have been observed making music, art or literature. Some have been seen draping themselves with greenery and flowers so perhaps fashion design predates the arts.

The fact that it is social animals alone who display similar behaviour to ours is the key. It has been suggested by Dawkins that “humans are nicer than is good for our selfish genes”. But we give help roughly at the same level as we need it; tigers are solitary animals who neither need nor give help, for example. Behaving pro-socially makes society work and affords the benefits of social living to the individual.

The fact that it is social animals alone who display similar behaviour to ours is the key. It has been suggested by Dawkins that “humans are nicer than is good for our selfish genes”. But we give help roughly at the same level as we need it; tigers are solitary animals who neither need nor give help, for example. Behaving pro-socially makes society work and affords the benefits of social living to the individual.

Being altruistic may make us feel good but feeling good has little survival value in itself, there must be another reason. Is it selfish to behave socially? Are we all really hypocrites? Is it selfish to care for our young, treat others well and to push to the front of the queue?

The big difference is that queue-jumping is a consciously chosen act whereas instinctive behaviour doesn’t involve thought. As De Waal has written, “Imagine the cognitive burden if every decision we took needed to be vetted against handed-down principles.” We may think about our impulses and choose whether or not to act on them but we do not need to learn or be forced to behave well. We often rationalise our moral decisions post hoc.

One section of the book which looks at atheism has been strongly criticized by some atheists, including AC Grayling, who accuse de Waal of being an apologist for religion. De Waal has said “While I do consider religious institutions and their representatives — popes, bishops, mega-preachers, ayatollahs, and rabbis — fair game for criticism, what good could come from insulting individuals who find value in religion?” and “I am all for a reduced role for religion with less emphasis on the almighty God and more on human potentials.”

This is hardly an apology for religion. It’s true that De Waal doesn’t like what he calls militant atheists or personal attacks on individuals who find comfort in their faith. He singles out Dawkins, Hitchens and Harris among others who, as AC Grayling says “aggressively argue the case for atheism”.

De Waal doesn’t think that all religious people are somehow defective, or ignorant or inferior thinkers. As a scientist, he is more interested in “what good it does for us. Are we born to believe and, if so, why?” and “For me, understanding the need for religion is a far superior goal to bashing it”.

I do take issue with De Waal’s speculation that atheism is the result of trauma. This may be the case for some people but others reach atheism through a mental process that leads them to reject belief. Some people never have a belief system in the first place. De Waal’s memories of the religion he grew up with in Holland contain no apparent trauma to explain his atheism and support this theory.

De Waal’s laid-back atheism may not be the ‘right’ kind, which raises the question: is there now only one atheism that is acceptable in public figures? He writes that the enemy of thought and science is dogmatism, whether political, religious or otherwise, because it shuts down discussion and sets up prophets who cannot be questioned. Does every scientist need to sing from the same hymn sheet as the arbiters of atheism (all white, middle class, old men)? Do they all need to be Dawkinses to be acceptable?

It’s important that this small part of the book does not detract from the whole. The lesson is that all of our behaviours are equally part of our nature, they are evolved and not unique to us. De Waal ends The Bonobo and the Atheist with: “Everything science has learned in the last few decades argues against the pessimistic view that morality is a thin veneer over a nasty human nature”.

Professor Frans de Waal is a Dutch primatologist working in America where he is the CH Chandler Professor of Psychology and the Director of the Living Links Centre at Yerkes Primate Research Centre at Emory University. He has been named as one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people. A leading expert on primate behaviour, he has written a series of books on it – including on morality, politics and empathy.

You can read an analysis of Grayling’s highly flawed argument here.

Tessa Kendall is a writer, researcher and campaigner, one of the organisers of London Skeptics in the Pub and Soho Skeptics.

Tessa Kendall is a writer, researcher and campaigner, one of the organisers of London Skeptics in the Pub and Soho Skeptics.

You can follow her on Twitter @tessakendall