This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 22, Issue 4, from 2011

Over the last three or four years, sceptics have redoubled their efforts to expose quacks, their twisted pseudoscience and their dodgy devices. This resurgence in scepticism is the latest round in a tradition of battling quackery that dates back to at least the eighteenth century.

For example, there was the effort to challenge the claims of Franz Mesmer. Whilst Mesmer is nowadays associated with hypnotism (or mesmerism), in his own lifetime he was most famous for promoting the health benefits of magnetism. He argued that he could cure patients of many illnesses by manipulating their ‘animal magnetism’, and one of the ways of doing this was to give them magnetically treated water.

The remedy was very dramatic, because sometimes the supposedly magnetised water could induce fits or fainting. Critics, however, doubted that water could be magnetised and they were also dubious about the notion that magnetism could affect human health. They suspected that the reactions of Mesmer’s patients were purely based on their faith in his claims.

In 1785, Louis XVI convened a Royal Commission to test these claims. The Royal Commission, which included Benjamin Franklin, designed a series of experiments in which one mesmerised glass of water was placed among four glasses of plain water – all five glasses looked identical. Unaware which glass was which, volunteers then randomly picked one glass of water and drank it. In one case, a female patient tasted her glass and immediately fainted, but it was then revealed that she had drunk only plain water. It seemed obvious that the fainting woman thought that she was drinking magnetised water, that she knew what happened when people drank such water, and that her body had responded appropriately. Once the experiments had been completed, the Royal Commission could see that patients had responded in a similar way regardless of whether the water was plain or magnetised, and it concluded that magnetised water was merely a figment of the imagination.

Closer to home, one of the first medical claims to come under close sceptical scrutiny concerned a set of medical devices known as ‘tractors’. These implements received the first medical patent issued under the Constitution of the United States in 1796 and were invented by a doctor named Elisha Perkins. At first glance they looked like nothing more than a pair of metal rods, but he claimed they could extract pains from patients.

The tractors were not inserted into the patient, but were merely brushed over the painful area for several minutes, during which time they would “draw off the noxious electrical fluid that lay at the root of suffering”. Luigi Galvani had recently shown that the nerves of living organisms responded to ‘animal electricity’, so Perkins’ tractors were part of a growing fad for healthcare based on the principles of electricity.

As well as providing electrotherapeutic cures for all sorts of pains, Perkins claimed that his tractors could also deal with rheumatism, gout, numbness and muscle weakness. He soon boasted of 5,000 satisfied patients and his reputation was buoyed by the support of several medical schools and high profile figures such as George Washington, who had himself invested in a pair of tractors.

The idea was then exported to Europe when Perkins’ son, Benjamin, emigrated to London, where he published The Influence of Metallic Tractors on the Human Body. Both father and son made fortunes from their devices: as well as charging their own patients high fees for tractor therapy sessions, they also sold tractors to other physicians for the cost of five guineas each. They claimed that the tractors were so expensive because they were made of an exotic metal alloy, and this alloy was supposedly crucial to their healing ability.

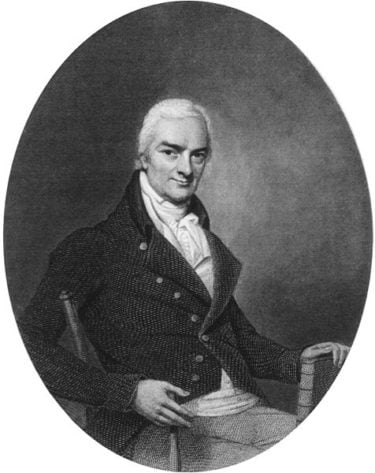

However, John Haygarth, a retired British physician, became suspicious about the miraculous powers of the tractors. He lived in Bath, then a popular health resort for the aristocracy, and he was continually hearing about cures attributed to Perkins’ tractors. He accepted that patients treated with Perkins’ tractors were feeling better, but he speculated that the devices were essentially fake and that their impact was on the mind, not the body. In other words, credulous patients might be merely convincing themselves that they felt better, because they had faith in the much-hyped and expensive Perkins’ tractors. In order to test his theory he made a suggestion in a letter to a colleague:

Let their merit be impartially investigated, in order to support their fame, if it be well-founded, or to correct the public opinion, if merely formed upon delusion . . . Prepare a pair of false Tractors, exactly to resemble the true Tractors. Let the secret be kept inviolable, not only from the patient but also from any other person. Let the efficacy of both be impartially tried and the reports of the effects produced by the true and false Tractors be fully given in the words of the patients.

Haygarth was suggesting that patients be treated with tractors made from Perkins’ special alloy and with fake tractors made of ordinary materials to see if there was any difference in outcome. The results of the trial, which was conducted in 1799 at Bath’s Mineral Water Hospital and Bristol Infirmary, were exactly as Haygarth had suspected – patients reported precisely the same benefits whether they were being treated with real or fake tractors. Some of the fake, yet effective, tractors were made of bone, slate and even painted tobacco pipes. None of these materials could conduct electricity, so the entire basis of Perkins’ tractors was undermined.

Instead Haygarth proposed a new explanation for their apparent effectiveness, namely that “powerful influence upon diseases is produced by mere imagination”. He argued that if a doctor could persuade a patient that a treatment would work, then this persuasion alone could cause an improvement in the patient’s condition – or it could at least convince the patient that there had been such an improvement. In one particular case, Haygarth used tractors to treat a woman with a locked elbow joint. Afterwards she claimed that her mobility had increased. In fact, close observation showed that the elbow was still locked and that the lady was compensating by increasing the twisting of her shoulder and wrist.

In 1800 Haygarth published Of the Imagination as a Cause and as a Cure of Disorders of the Body, in which he argued that Perkins’ tractors were no more than quackery and that any benefit to the patient was psychological – medicine had started its investigation into what we today would call the ‘placebo effect’.

The word ‘placebo’ is Latin for ‘I will please’, and it was used by writers such as Chaucer to describe insincere expressions that nevertheless can be consoling: “Flatterers are the devil’s chaplains that continually sing placebo”. It was not until 1832 that ‘placebo’ took on its specific medical meaning, namely an insincere or ineffective treatment that can nevertheless be consoling.

Importantly, Haygarth realised that the placebo effect is not restricted to entirely fake treatments, and he argued that it also has a role to play in the impact of genuine medicines. For example, although a patient will derive benefit from taking aspirin largely due to the pill’s biochemical effects, there can also be an added bonus benefit due to the placebo effect, which is a result of the patient’s confidence in the aspirin itself or confidence in the physician who prescribes it. In other words, a genuine medicine offers a benefit that is largely due to the medicine itself and partly due to the placebo effect, whereas a fake medicine offers a benefit that is entirely due to the placebo effect.

As the placebo effect arises out of the patient’s confidence in the treatment, Haygarth wondered about the factors that would increase that confidence and thereby maximise the power of the placebo. He concluded that, among other things, the doctor’s reputation, the cost of the treatment and its novelty could all boost the placebo effect. Many physicians throughout history have been quick to hype their reputations, link high cost with medical potency and emphasise the novelty of their cures, so perhaps they were already aware of the placebo effect. Nevertheless, Haygarth deserves credit for being the first to write about the placebo effect and bringing it out into the open.

Today, despite the rise of science and breakthroughs in medicine, quack therapies, quack theories and quack devices are still widespread, partly because they continue to skillfully take credit for the placebo effect. Hence, it is to the credit of the sceptical community that we continue to challenge these therapies, theories and devices, while those who should be taking action stand idly on the sidelines.

For example, while the Government tolerates the funding of bogus therapies such as homeopathy, it is crucial that campaigns such as 10:23 try to inform the public about the reality behind these sugar pills. Also, we hope the Nightingale Collaboration, which only started this year, will play an increasingly important role encouraging the public to use the existing framework of legislation and guidelines to remove misleading claims. Such examples of sceptical activism help protect patients who might otherwise waste their money on treatments that are not only ineffective, but also potentially dangerous.

This edition of The Skeptic contained a special selection of articles about quackery and anti-quackery activism. It is reassuring to see that the spirit of John Haygarth lives on, but sad that such quack-busting is necessary in the twenty-first century.