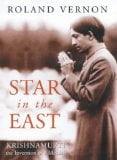

Star in the East: Krishnamurti, the Invention of a Messiah

Star in the East: Krishnamurti, the Invention of a Messiah

by Roland Vernon

Constable, £20, ISBN 0094764808

What happens if you are trained from childhood to be a religious leader, and then lose your faith? The life of Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986) suggests that one solution is to stay with the occupation which you’ve trained for – and continue as a religious leader.

Krishnamurti was born in India, the son of an impoverished Brahmin. At the age of 13, he became the protégé of Charles Leadbeater, a prominent (and somewhat shady) Theosophist, and was groomed for the role of World Teacher, first in the Theosophists’ Indian settlement, and later in England.

However, in his twenties, he became increasingly skeptical about Theosophy, and, in 1922, following a love affair with an attractive young woman, he experienced a major physical and psychological crisis. This led him, over the next few years, to break with the Theosophist moment, abandoning its weird and complex mythology in favour of his own, more abstract, ideas.

Supported by wealthy patrons, and by an entourage of devotees, he continued to teach and to write for more than 50 years, appealing particularly to the kind of Westerner who has religious yearnings, and who looks to the East to have them satisfied. Although, in some respects, an egotistical, indeed infantile person (something which his biographer does not try to conceal), his failings were no worse than might be expected of someone with his upbringing. Certainly, his lifestyle seems to have avoided the excesses of some recent religious leaders. Although it contains some fascinating material about the history of Theosophy, this book will appeal mainly to those who take Krishnamurti’s teachings seriously.

Unfortunately, the author makes little attempt to explain or paraphrase these, presumably because Krishnamurti himself expressly forbade anyone to do so – and for obvious reasons. Unless treated as Holy Writ, and approached with reverent humility, Krishnamurti’s writings appear to be little more than windy pantheistic rhetoric. He tells us that external facts are of no importance (so the whole of science is of no account). Nor are our thoughts of any importance (though Krishnamurti) could scarcely have had the career he did unless he made an exception in favour of his own thoughts). Instead, we are to rely on “pure observation which is insight without any shadow of the past”. This will lead us to see that “the division between the thinker and the thought, the observer and the observed, the experiencer and the experience … is an illusion.” And so on. . . . One reader, at least, is underwhelmed by such “wisdom”.

Nevertheless, despite the unpromising material, Roland Vernon has produced a well-written and thoughtful book. Indeed, it is, perhaps, a better biography than its subject deserves.