This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 18, Issue 3, from 2005.

In the 1950’s the English town of Esher was apparently subjected to a three-year reign of terror by a phantom sniper. This lone gunman is alleged to have shot at dozens of motorists as they passed through the town, smashing their windscreens and causing other damage. No bullets or other missiles were found that could account for the damage and, despite a police manhunt, no suspect was ever brought to book.

The shootings raised serious concerns in the local community and the story even managed to make it into the national press. Despite its brief moment of fame, the actions of the phantom sniper were quickly forgotten and would have likely escaped attention altogether if the authors hadn’t spotted a reference to it in the book Stranger than Science written by Frank Edwards in 1959.

Edwards’ brief report led the authors to track down further references and eventually to uncover a whole series of events that, as far as we know, have remained hitherto uncommented upon by social historians. We will, over three issues of The Skeptic, fully document the Esher phantom sniper incidents, offer an explanation as to their cause, and briefly compare them to other similar incidents world-wide.

The start of the trouble

Esher is a small town located on the outskirts of south-west London in the county of Surrey. It is an ancient settlement built around an old Roman road which is now a major highway. This road, known as the Portsmouth Road or the old A3, runs north-south through Esher’s town centre and is a direct link between London and the south coast cities of Brighton and Portsmouth and was the focus of the phantom sniper incidents.

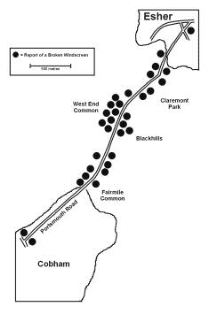

The geography and population of this region has changed little since the early 1950s. Although a bypass road, built in the 1960s, takes much of the traffic away from Esher, the Portsmouth Road remains a busy thoroughfare. The focus of the phantom sniper incidents was a 4 km stretch of the Portsmouth Road that runs between Esher in the north, to the town of Cobham in the south. Despite high population densities in the Surrey region, this stretch of road runs through largely unpopulated heath and common land before reaching the outskirts of Cobham. Other incidents mostly occurred in the more populated area to the north of Esher either on the Portsmouth Road or on some of the other large routes linking the Portsmouth Road with other London satellite towns such as Kingston, Surbiton and Thames Ditton.

The story of the phantom sniper is almost exclusively documented through the pages of The Esher News and Advertiser (ENA), a local weekly paper that was to become obsessed with this mystery. The ENA’s first mention of the phantom sniper comes from its edition of 12th January 1951. Under the title Hell-Fire Pass? a brief article mentions that since the beginning of December there had a been a spate of car windscreens being spontaneously shattered on the same short stretch of the Portsmouth Road between the towns of Esher and Cobham. The road had been nick-named by some motorists as ‘Hell-Fire Pass’. The ENA lists three incidents and interviews one of the drivers, a Mr H Tickner of Esher, whose description of his experience would come to characterise those of many people in the months to come:

On Tuesday morning Mr Tickner, of 90, High-Street, Esher, was driving his car towards Cobham when, as he was passing along the Fairmile, he saw a sudden flash, heard an explosion and his windscreen was starred so much that he was forced to pull up. A piece of the windscreen the size of a sixpence fell inside the car, and the spring holding the licence holder in position was shot on to the back seat. At the time no cars were coming towards him, but one had just passed him on the way to Cobham. He got out of the car, but could find no trace of any missile.

The other two witnesses are not interviewed but it is significant that the first person that the ENA cites as having been a victim of the sniper is the political journalist and well-known broadcaster Richard Dimbleby. The article indicates that Mr Dimbleby’s experience was well-known stating that: “it will be remembered that early last December Mr Richard Dimbleby, the well-known broadcaster, reported to Esher police that his windscreen had been hit, and it was at first supposed the missile was a .22 bullet”.

In a later article the ENA again asserts that the first acknowledged smashed windscreen was that of Richard Dimbleby, and gives an exact date of the 2nd December 1950 for the incident. Given the national fame of Mr Dimbleby, we wondered whether his encounter might not have been reported in other local or national papers. However, a search produced only one very brief mention of the incident in the 8th December edition of the London Evening Standard in which, at the bottom of an article about a BBC coach being hit by a bullet near Birmingham, it adds that: “recently Sonia Holm and her husband, and Richard Dimbleby were shot at when travelling in their cars”.

The recognition that there may be a serial sniper at work on ‘Hell-Fire Pass’ led to the ENA running two further articles on smashed windscreen incidents on the 26th January and 9th February 1951. In these articles it lists another four incidents to have occurred along ‘Hell-Fire Pass’ and speculates that either a sniper or loose stones on the road could be responsible. An editorial requests that either the highway authority or the police look into the issue as a matter of urgency. After this there is a break in the coverage of these incidents of several months.

The height of the panic

A sustained number of sniper incidents began on the 15th December 1951 when Mr S Jay, a teacher from Cobham, was driving south along the Portsmouth Road when he “heard a crack like a pistol and saw his complete windscreen frost over”. This was again covered by the ENA which blames a person with a “catapult, air-gun or a .22 rifle”.

Mr Jay’s smashed windscreen was to be the beginning of a prolonged period of local, and eventually national, interest in the strange happenings along the Portsmouth Road. By the 11th January 1952 the ENA had recorded 12 sniper incidents from the same stretch of the Portsmouth Road. By mid-March this total had risen to 14 and the nature of the ENA’s reporting had taken on a more serious tone with one article asking the authorities: “When will action be taken to end this menace at Esher?”

By now the ENA was firmly backing the idea of a sniper with an airgun being responsible, a position that would seem to be justified by the incident that occurred on the 20th March. On this date a Mr Frank C Smith from Thames Ditton was driving north along the Portsmouth Road when he “felt the car rock and pulled up to find out what happened”. On examining his car he was shocked to find a 9 mm hole in the driver’s door, about 8 cm below the door handle. It appeared as though somebody had taken a pot shot at him. The ENA ran a picture of a worried looking Mr Smith sitting in his damaged car and commented on the case:

A ballistic expert has since said that it was probably a .317 bullet, an unusual calibre for a British gun, but one quite common in Italy. If it was fired from a high bank along the side of the road, it might have ricochetted [sic] off the road surface before hitting the panel. If the gun had been aimed at the door, the bullet would have killed the driver.

Mr Smith’s incident marks a turning point in the history of the phantom sniper. From this moment on the concerns of the ENA and the local community were to be taken seriously by the police and the local council.

After the next series of smashed windscreens, which were reported within two weeks of Mr Smith’s shooting, the police began to patrol the Portsmouth Road and even instigated a detailed search of the surrounding common land. However, this did nothing to lessen the activities of the phantom sniper and by the 16th May the ENA had recorded a total of 20 incidents. It was at around this point that interest in the happenings at Hell-Fire Pass began to attract attention from outside the region. The shattered windscreen of Mr Eric Sykes, which occurred on the 9th May, is the first of the phantom sniper incidents to make it into the back pages of the London Evening Standard where the newspaper glibly states that the police are “looking for someone with a gun”.

During the following weeks yet more reports of damaged cars came flooding in. For the first time a car windscreen was shattered, not on the Portsmouth Road, but a couple of kilometres to the east on Copsem Lane which leads into the town of Oxshott. Not only was the phantom sniper spreading further afield, he was also becoming more adventurous in his shooting, hitting not only windscreens but also the headlights of an ambulance and a private motorist. In the light of these revelations the local council swept the Portsmouth Road between Esher and West-End Lane in the hope that loose stones, and not a gunman, might be the cause of the trouble.

The first national coverage came at this time in the form of an article which is referred to by the ENA. We could not track down where this national article was published, but the ENA reports that it put forward the idea that the sonic boom from low flying aircraft might be to blame. In an editorial on the matter, the ENA comments on this idea and ultimately rejects it in favour of a lone gunman stalking the Portsmouth Road. It also summarises its involvement in the development of the phantom sniper mystery:

Months ago, when we started to report it, we were alone. Then, via the county and evening Press, the affair reached the nationals. Last month, over eighteen months after the first incident, Esher Council took official notice of the matter. We are now waiting with bated breath for a question to be asked in Parliament. That, our readers will be interested to learn, is how the machinery of democracy creaks to an ultimate solution. But what an awful time it takes!

Again, incidents of broken windscreens kept on being reported but the sniper was also being held responsible for other crimes too, including the smashing of a shop and a pub window in Esher itself. Some of these incidents were accompanied by intense police activity, such as the broken windscreen of Mr V J Wood, which prompted ten constables to search surrounding woodland and undergrowth.

Complaints from local residents spurred the council to demand a statement from the Metropolitan Police on their plans to catch the sniper. “The ratepayers are entitled to know what actions are being taken,” wrote councillor N. Jones. The request eventually produced a reply from the Police Commissioner who said that a “special observation had been kept on the road by selected officers, and would be continued for a further period, but that at present there was no evidence to support the theory that the damage was being caused maliciously”. It was also mentioned that the Ministry of Transport had plans to investigate the matter. It is clear from these statements that the Metropolitan Police did not favour the sniper theory, but instead looked more kindly on the idea of loose stones causing the damage. Members of the council disagreed, and during a debate on the matter several councillors expressed their concern at the police’s attitude towards the problem. Councillor E Royston said, “There is a solid basis of concern, and it would be wrong for us to shrug our shoulders or laugh at it, and wrong to say that we know what the cause is”.

By September 1952 the number of incidents had reached at least 33 but there was yet to be found a single bullet, pellet or other missile in connection with these broken windows. To explain this, readers of the ENA were coming forward with their own theories including catapults, falling pine cones, and pellets made from frozen carbon dioxide (dry ice) that would melt on contact. Following attention from the national press, the police and the council, local interest was probably at a maximum during the period between May and September, but it was to tail off at the beginning of

October when the number of articles in the ENA decreased in number. It is noticeable that during August to October the reports of shattered windscreens came from not only the Portsmouth Road, but also from surrounding areas including East Molesey, Thames Ditton and Hinchley Wood. Between the 16th October and 1st December 1952 there were no reports of shattered windscreens at all, the longest period of quiet in nearly a year.

The final phase

The six weeks of quiet from the phantom sniper of Esher was in fact only a lull before he committed himself to one final burst of activity. In December 1952 five reports of broken windscreens were recorded in the ENA. More incidents in January begged the ENA to ask if a new phase of shootings was beginning, but despite this blip in activity, the number of reports was to only be a trickle in comparison to the previous year with the most serious incident being four windscreens shattered in the same week in April.

Other theories continued to be put forward. In February the Metropolitan Police informed the council that “in spite of intensive observation over a prolonged period, the police have no evidence that the damage is being caused maliciously”. In other words the police did not favour the sniper theory. Other theories were not so cautious. Gordon Slyfield wrote to the ENA to suggest an esoteric solution to the mystery:

The metaphysical theory must not therefore be ruled out. I am familiar with the physical results attached to psychical phenomena of the séance room. If there is a powerful spiritualist medium dwelling on this road, he or she may be ignorant and need not go into a trance… A rod of ectoplasm proceeding from the medium is strong enough so that an entity can lift physical objects. This is what happens with poltergeist phenomena in the presence of adolescents.

If such an entity were the spirit of a dastardly highwayman, might not he still operate against lawful users of the highway? It may therefore be a case for the Institute of Psychical Research to lay an unhappy spirit.

In a reply to this, G Bird says: “Why stop at earthbound highwaymen firing ectoplasmic bullets; why not the vibrations of harps twanged by little men landing from flying saucers?” Mr Bird goes on to express local belief in a gunman and suggests that local patrols could be the answer to catching the culprit. These debates in May 1953 largely mark the end of the incidents on the Portsmouth Road. After this time there was only to be another five reports of broken windscreens, three of which did not occur in the local region. As the number of weeks increased between articles, one definitely gets the impression that local interest in the matter had died, and the ENA was reduced to making the odd report near the back of the paper. The last report is from their 11th December 1953 issue, when a Mrs L Perry reported having her windscreen shattered while driving in Ealing, a location many kilometres north-west of Esher. There was also a brief mention in FATE of aeroplane windscreens being broken whilst flying over Esher, but no further references could be found for this.

By our reckoning the phantom sniper of Esher was active over a period of almost exactly three years, during which time at least 51 individual incidents were recorded. A single bullet was never recovered, nor a culprit seen, let alone apprehended. Interest in the mystery was rapidly forgotten, although a series of articles did appear on it in FATE magazine upon which Frank Edwards wrote a small section for his book Stranger than Science which was in turn the basis of one further article in the Fortean Times.

So, after three years of intense activity by both the sniper and the press, the mystery was no nearer to being resolved. Who or what was breaking the windscreens? There was no shortage of theories, both rational and irrational, and these will be the subject of our next article.